SHAKUNTALA

Introduction by Michael Dolan, B.V. Mahāyogī

Kālidāsa's

accomplishment in the composition of this work is indeed masterful, and in the

opinion of many great scholars surpasses the original tale in the Mahābharata,

both for lyricism and poetry as well as for the depth of his romantic vision.

My own gurudeva, His

Divine Grace Bhakti Rakṣaka Śrīdhara Dev Goswāmī, who was known for his

erudition in Sanskrit as well as for his philosophical wisdom in Gaudiya

Vaishnava siddhānta, particularly loved the poetry of Kālidāsa,

representing as it does the best of ancient Indian culture and the highest

virtures of Sanskrit drama. While it may be seen by some as merely a fairy tale

or romance, the story of Shakuntala not only contains elements of drama far in

advance of Shakespeare, but also delineates the moral and religious precepts of

ancient India as shown in her mythology and spiritual culture.

The story is often given

summary form by story-tellers who cover the basic plot points, redacting

severely the poetic sense of the work. In the interest of brevity, I am unable

to give full justice to Kalidasa, but have tried to include some of his more lyric

turns of phrase.

My particular retelling

is a work in progress; I began constructing this version after going through

various translations of Mahābhārata, particularly that of Kishori Mohan Ganguli

(http://www.gutenberg.org/files/15474/15474-h/15474-h.htm)

long considered the most authoritative, for it is the only translation of all

100,000 Sanskrit verses into English.

Of course, the version

of Kalidas varies with that of Mahābhārata, and for this I have consulted both

the translations made my Monier Monier Williams of Sanskrit dictionary fame as

well as that of Arthur Ryder. (http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1261)

These versions are in the public domain and may be found at Gutenberg.org.

However the language of these translations is circuitous and Victorian and

sounds to my ear quite out-dated. The Sanskrit drama runs to more than 100

pages in translation and is difficult to follow, but for anyone who likes a

deeper study of the work, it's worth the read.

Introduction by Michael Dolan, B.V. Mahāyogī

The story of Shakuntala

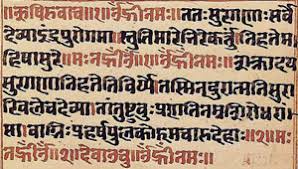

is related in the Adi Parva of Mahabharata महाभरत, and retold centuries

later by the great Sanskrit poet Kālidāsa probably in around the 5th century in

his literary play, Abhijñāna-śākuntala, अभिज्ञानशाकुन्तल. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shakuntala

Kālidāsa's

accomplishment in the composition of this work is indeed masterful, and in the

opinion of many great scholars surpasses the original tale in the Mahābharata,

both for lyricism and poetry as well as for the depth of his romantic vision.

My own gurudeva, His

Divine Grace Bhakti Rakṣaka Śrīdhara Dev Goswāmī, who was known for his

erudition in Sanskrit as well as for his philosophical wisdom in Gaudiya

Vaishnava siddhānta, particularly loved the poetry of Kālidāsa,

representing as it does the best of ancient Indian culture and the highest

virtures of Sanskrit drama. While it may be seen by some as merely a fairy tale

or romance, the story of Shakuntala not only contains elements of drama far in

advance of Shakespeare, but also delineates the moral and religious precepts of

ancient India as shown in her mythology and spiritual culture.

The story is often given

summary form by story-tellers who cover the basic plot points, redacting

severely the poetic sense of the work. In the interest of brevity, I am unable

to give full justice to Kalidasa, but have tried to include some of his more lyric

turns of phrase.

My particular retelling

is a work in progress; I began constructing this version after going through

various translations of Mahābhārata, particularly that of Kishori Mohan Ganguli

(http://www.gutenberg.org/files/15474/15474-h/15474-h.htm)

long considered the most authoritative, for it is the only translation of all

100,000 Sanskrit verses into English.

Of course, the version

of Kalidas varies with that of Mahābhārata, and for this I have consulted both

the translations made my Monier Monier Williams of Sanskrit dictionary fame as

well as that of Arthur Ryder. (http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/1261)

These versions are in the public domain and may be found at Gutenberg.org.

However the language of these translations is circuitous and Victorian and

sounds to my ear quite out-dated. The Sanskrit drama runs to more than 100

pages in translation and is difficult to follow, but for anyone who likes a

deeper study of the work, it's worth the read.

|

So in my retelling here

on the blog I have included ample illustrations from various sources: Movie

posters, TV shows, still photos of dramas, Iskcon paintings, and the excellent

artwork of Raja Ravi Varma.

| Ravi Raja Varma, Indian Artist, Victorian Period |

I have no particular

permission to use these different illustrations. But since my blog is not

commercial and is for educational purposes only, I see no harm in including

different paintings and drawings in different styles to bring the reader closer

to the story.

| Curse of Durvasa. |

As a blogger, I'm

inviting my readers to journey with me through the creative process and the tremendous learning curve I face, as story-teller and cybernaut. This

retelling is undergoing editorial change on a regular basis; when it is

finished it may take on a more formal aspect and be published as a book or

graphic novel. At the present moment I have taken this on more or less as a

hobby, something that might entertain my many friends and readers around the

world.

I have been publishing

this as a serial, a few paragraphs a day, for two reasons: one, to allow the

reader to get involved in the story a little bit at a time, and two, for the

purpose of editing gradually what I began last year as a larger project, the

retelling of the entire Mahābhārata.

| Mahabharata |

I thank you all for your

patience in reading. I sincerely hope you enjoy this version and that it allows

you to reflect on the traditions and wisdom of ancient India on your path to

truth. I hope that my humble attempt to retell the stories found in these

great classics brings you some light.

Humbly,

Michael Dolan, B.V.

Mahayogi

Shakuntala

Remembering

the vow of vengeance taken by Amba, Bhishma paused. The mysterious brahmaṇa boy

who had attended Bhiṣma drew some water onto a cloth. Wringing it out he wiped

the perspiration from the old man’s head. Bhishm coughed. "I grow weary

with this tale," He said. The sun had dipped below the horizon. Venus

appeared in the heavens. "Let me rest a while."

"We

shall return to you in the morning," said Yudhisthira "The history of

our dynasty is filled with many lessons. We are eager to hear more."

"Go

now," said Bhishma. "Tomorrow I shall tell you of how Amba was

transformed by fire into a warrior in the family of Drupada and how I met this

terrible end.

Go

now and may your stars guide you."

The

Pandavas returned to their camp. The brightly colored tents looked faded in the

light of the campfire.

Nakula

and Sahadeva took their places by the fire and were joined by Arjuna and Bhima.

After so much battle, finally a moment of peace. Now Venus had been joined with

a thousand stars and their pinpoints of light shined in the heavens above

Kurukshetra. Yudhisthira appeared with Kuntidevi their mother. And as they sat

around the fire and watched the planets move through the sky, the conversation

turned to the ancient dynasty of the Kurus.

The

long war was over. Asvatthama had been banished. The ghosts of dead warriors

stalked the battlefield, but their chariots would no longer clatter over the

earth. No longer would thousands of car-warriors terrorize the towns and

villages around Hastinapura. India would know peace under the reign of

Yudhishtira, Pariksit, Janamejaya and subsequent kings of the Bharat dynasty.

As the fire burned low, the modest Yudhisthira turned to his mother Kuntidevi

and before the Pandavas seated there asked her, "O Mother. Bhishma spoke

of Vichitravirya and Chitrangada, our ancestors. Tell us of our ancestors. We

are called the sons of Bharata. Tell us of the origins of the Kuru

dynasty and of Bharat Who was Bharat? What were his origins."

The

wise and expert Kunti explained. “The Kuru dynasty comes in the line of Bharat,

who was born in the line of Puru. To better understand this history I must tell

you the story of Shakuntala.”

The Story of Shakuntala

And so it was that

Kunti told them the famous story of Shakuntala as she had heard it when

she was only a girl in the court of King Kambhoja. She spoke as follows:

“Once upon a time there

was a great king. His name was Dushyant and he came in the line of Puru.

One day Dushyant was

hunting with his charioteer in the deep forest and he came upon a spotted deer.

The deer ran away, leading Dushyant and his charioteer deeper into the

forest.

| Deer hunting: Irainian miniature |

They chased the spotted

deer futher into the deep woods with Dushyant tracing his movement with

his bow. Just as Dushyant was ready to unleash a fatal arrow, a young monk from

the nearby ashram of Kanva, appeared before him, with hands raised in supplication.

He said, ‘Please don’t shoot. O king or prince, whoever you are, please spare

the life of this spotted deer.

This deer is the

favorite pet of our guru, Kanva. You are close to the ashram of Kanva. Here

there is no hunting; only peace. The disciples of the humble Kanva live

quietly contemplating the truth. The nimble spotted deer is sacred to Kanva and

his disciples. Please don’t shoot. Rather put down your weapons in the spirit

of ahimsa.’

With this, the king,

still flushed with the heat of passion and eager for blood, steadied his mind,

unstrung his bow and smiled. “If this fawn is the favorite of a holy man and

his friends, so be it. I shall never harm an innocent animal. Tell me again of your

master and his ashram. Let us speak of truth and peace. We shall have no more

violence and blood sport.”

The monk thanked the

king and praised him. “Our ashram is near here,” he said. “Follow the bank of

the river to the holy tirtha. Just there, nearby is a grove of tamarind trees

above the river’s bank. Within that secret grove you will find the shelter of the

holy Kanva and his disciples. Thank you again for your noble grace. I see that

you are a great prince and the protector of the harmless. If it pleases your

Lordship, why not stay for prasadam, our sacred food?”

| Kanva Muni at his ashram |

Bidding farewell to the

monk, he gave orders to his man to drive the chariot a little farther on into

the woods where there would be water for the horses. They drove for a while

until they found good green pasture by the side of the river, and the water flowed

clear and sweet.

The king gave orders to

his man. “Untie the horses and let them roam or rest for a while as they will.

See that they eat the cool grass of yonder pasture and find shade in those

those tamarind trees. I will stretch my legs, and after walking a while, visit

the ashrama of the saint Kanva, to pay my respects. If I am not back by sundown

I will rest in the ashram and return in the morning.”

Shakuntala

at Kanva's ashram

|

His horse-man agreed and

took the chariot a little farther on into the woods. King Dushyant

decided that his son’s birthday party could wait and thought that it might be

auspicious to pay a visit to the ashram of the saint Kanva. He began to walk a

while and enjoy the quiet atmosphere of the forest. A butterfly hung in the air

before him. The fragrance of honey permeated the air. He walked through the

tall trees by the river where the cranes fished in the early morning. The air

was fresh and the river low, the rainy season having passed.

King Dushyant had

understood from the monk where the ashram would be and so he crossed the river,

wading through a shallow point. On the other side of the river he found the old

holy tirtha with its deities and a bathing ghat with rich marble steps by a grove

of tamarind trees.

As he followed the path,

the grove of trees became thicker with creeping vines that flowered with

jasmines. A tall mango tree shaded his path where up ahead between the vines he

saw a clearing. In the clearing were a few small bamboo huts and a path. There

was a rustic garden with papayas and some women were working, watering the

plants and talking. Surprised by such an enchanting garden where he had

expected the austere quarters of an old saint, King Dushyant stopped awhile by

the mango tree and hid himself, listening. He could hear the women of the

ashram talking.

Shakuntala

in the ashrama of Kanva Muni with deer

|

“Where has Kanva Prabhu

gone?” said one of the girls, Priyamvada.

“He told me, Anasuya,

that he had to visit a very sacred place in the forest.”

“But, Priyamvada, why

would he leave today if he knows that we have an important sacrifice tonight?”

“I can’t tell you,

Anasuya. He told me not to tell anyone.”

“But if you can’t trust

me, who can you trust?” said Anasuya.

“Well all right, but

don’t tell Shakuntala.” said Priyamvada. “It has to do with her. Something

about her good fortune.”

“I worry about that

girl,” said Anasuya.

“Me too,” said

Priyamvada. “Kanva loves her as if she were his own daughter.”

“But Kanva isn’t her

father, is he?”

“Of course not, silly. She was adopted by Kanva. Her mother left her when she

was only a baby. It was a big mystery.”

Shakuntala

at the Ashrama of Kanva Muni by Raja Ravi Varna

|

“Her mother was Menaka,

the apsara, I heard. Didn’t she have something to do with Vishvamitra?”

“I’ve told you the story

a million times. Vishvamitra was a great warrior who was determined to become a

powerful brahmaṇa after he saw what the miracle cow of Vasistha could do.”

“So?”

“So he was practicing

austerities and penances for a long time, until even the gods were afraid of

him.”

“What did they do?”

“Well, when they saw him

practicing a powerful kind of yoga, they realized he was following a strict vow

of brahmacharya.”

“Brahmacharya?”

“Yes, silly, that’s when

you give up women. Anyway, there he was on the banks of the Ganges practicing

yoga and the gods decided to break his vow.”

“Why would they do such

a thing?”

“Vishvamitra was

becoming too powerful. If they didn’t break his vow he would become as powerful

as the gods.”

“How did they break his

vow?”

“They sent the most

beautiful of all the river nymphs, the delicate Menaka. Her beauty was

reknowned amongst the gods. No man could resist. Vishvamitra was sitting there,

practicing his yoga. To disturb his concentration, Menaka the water nymph came

to the banks of the Ganges and began to bathe in a fine silk sari, smiling all

the time at the sage.”

In the forest ashram of the sage

Kanva, the girls were gossiping.

“Brahmacharya?”

“Yes, silly, that’s when you give

up women. Anyway, there he was on the banks of the Ganges practicing yoga and

the gods decided to break his vow.”

“Why would they do such a thing?”

“Vishvamitra was becoming too

powerful. If they didn’t break his vow he would become as powerful as the

gods.”

“How did they break his vow?”

“They sent the most beautiful of

all the river nymphs, the delicate Menaka. Her beauty was reknowned amongst

the gods. No man could resist. Vishvamitra was sitting there, practicing his

yoga. To disturb his concentration, Menaka the water nymph came to the banks

of the Ganges and began to bathe in a fine silk sari, smiling all the time at

the sage.”

Just as Priyamvada was about to

finish her story about Shakuntala’s mother, the fair Shakuntala herself,

appeared in the mango grove carrying a clay water pot on her head. Her bare

feet barely touched the ground as she walked, so delicate was she, as beautiful

and graceful as the first lotus flower of spring.

As she joined her friends,

Shakuntala said, “Am I interrupting anything?” She smiled, her bee-black hair

shining in the afternoon sun.

Her dear friends and fellow

inmates of the ashram, Anasuya and Priyamvada giggled. "No, we were just

talking,"

And joyful in springtime, they

went about their duties, watering the papaya plants.

Observing them through the green

leaves of the tamarind trees was Dushyant the descendant of Puru. He now

smiled to himself in the shadow of the mango tree. The ashram of Kanva was the

ideal place for the contemplation of peace and the harmonies of the universe.

Now, it was time for him to make his entrance.

He made a great noise as if he had

just arrived through the tamarind trees. King Dushyant walked up the path to

the clearing in the mango grove. The jasmine flowers made the air heavy

with their fragrance. Moving with an exuberant royal swagger he called out,

“Hello! Is anyone here?, O Kanva! Is this the ashram of the great saint

Kanva?”

“Kanva is not here,” the ladies

answered. “He has gone on pilgrimage. Who is there?”

Not wanting to reveal himself as

the king and royal liege of the forest, Dushyant replied,

“You are welcome,” said

Priyamvada. “If you have protected the life of our fawn, then you are as

welcome as any saint. Please stay and honour our prasadam. It is humble but

will bless you with long life, as the food here is sacred.”

“I agree. I thank you and salute

you all. When will the sage Kanva return?”

“We expect he will return before

the ceremony tomorrow. Stay with us a while and allow us to offer you our

hospitality,” said Anasuya, smiling. As the bees plucked honey from the

yellow orchids near the mango tree, King Dushyant noticed the elegant young girl

who shyly watered the papaya plants and kept her distance. Following his

glance, Priyamvada smiled and said, “Allow me to introduce Shakuntala.

Shakuntala, don’t keep our visitor waiting, bring him water and a sitting

place of the finest kusha straw.”

The fair and shy Shakuntala didn’t

raise her eyes or look directly at the king. She went to fetch more

water with the clay pot that he held on her head. Her hips swayed gently as

she left for the river by the holy bathing ghat.

“Shakuntala is shy,” Priyamvada

said. “Tell us, where is our fawn? Did you frighten him away?” King Dushyant

told the story of the hunt, but changed it making himself the charioteer.

“So where is our king?” she said

eagerly.

“The king has returned to his

entourage deeper in the woods. I left the chariot and horses not far from

here, to rest and take water. Soon I must return. Give my respect to the

saint who attends you all so well in this ashram.”

In a few minutes Shakuntala returned

with water and sitting places for all.

The sun had begun its climb into

the heavens and the heat of the day began in earnest. So they sat under the

welcoming shade of tamarind and mango trees by the papaya garden while the

honey-bees busied themselves dancing amongst the champak flowers while kokil

birds gave their afternoon concert. There in the comforting shade Shakuntala,

Priyamvada, and Anasuya drank cool refreshing drinks of rosewater and mint

with the king as the ladies described the mission of Kanva and his teachings.

As the sun grew even warmer and

more time passed, Priyamvada and Anasuya detected a certain affection between

the king and Shakuntala. Smiling to herself Priyamvada said, “You must excuse

us now, for we have many duties to perform and the sun is sitting low on the

horizon. Come Anasuya. Let the fair Shakuntala explain the precepts of our

guide Kanva to the king’s officer.”

“I too have many duties to

perform,” protested Shakuntala, her face at once turning red as a rose.

“We must not violate the

principles of hospitality,” said Priyamvada, with a firm smile. “You stay

here with the king and explain the holy nature of this refuge in the forest.

We shall return shortly.”

So they sat together, Shakuntala

and King Dushyant and as the sun went down they laughed and talked of

everything.

The king was lost in her company

and felt he had never been so charmed before in his life as when he saw the

deep eyes and bee-black hair of the shy but charming Shakuntala. As the sun

finished its glorious arc, the first star appeared on the horizon. The kokil

birds once again took up the song they had left in the morning and began

their vespertine concert. Just as Dushyant and Shakuntala were becoming even closer

in thought and feeling, they heard a terrible noise. Something was

thrashing through the jungle, upsetting trees and animals.

A terrific trumpeting noise

alarmed the birds who flew away. A enraged male elephant was rampaging

through the grove, missing his mate. Priyamvada and Anasuya came running back

to the place where Shakuntala and Dushyant sat. They were in a panic.

With them was Gautami, the matron of the ashram. “The elephant is mad! He may

attack at any minute,” said Gautami. “We must run or take shelter. He may

destroy the bamboo hut of Kanva. Hurry!”

Everyone was afraid of the great

bull elephant who rampaged through the forest overturning trees. Rising to

his feet, the great King Dushyant touched the sharp sword on his left hip

with his right hand and assuaged the ladies there. “By the power of my right

hand, I shall defend you and the ashram of Kanva. Wait behind those trees.”

He said.

The ladies hid behind the

tall mango tree and prayed to Vishnu for protection from the beast who ran

through the forest.

|