Why Read Books?

In Defense of the Bhagavat

by Michael Dolan/B.V. Mahayogi

[Sorry for the length of these articles but I find it difficult to be concise...]

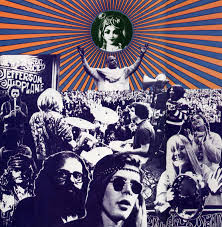

Back in the 1960s I was different from most of the kids in high school. While they were getting ready to fight the cold war and support the troops in Vietnam, I studied Russian and learned to play the songs of Bob Dylan at the guitar. We all admired our teacher. He had been in World War II and encouraged us to think for ourselves. While nominally we were studying languages, sometimes he let us discuss ideas.

One day we noticed a book by J. Krishnamurti on his desk and asked him about it. After some discussion with our classmates I had some more questions and he let me borrow the book.

Krishnamurti used to teach that meditation is the mind emptying itself of its own content. There is no need for books or teachers, but only to look at ourselves with great attention and care. I found it ironic that Krishnamurti wrote a book to explain that we don’t need books.

Growing up, my generation had a lot of cultural heroes like Krishnamurti. Another one of our heroes was Alduous Huxley who coined the famous phrase “Doors of Perception,” which inspired Jim Morrison and company to form their L.A. rock band, “The Doors.” As good poets steal where bad poets only copy, the expression “Doors of Perception really derives from England’s first Psychedelic poet, William Blake, who in a poem called the “Marriage of Heaven and Hell” once wrote:

“If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' narrow chinks of his cavern.”

Huxley appropriated Blake’s phrase to describe his experience of taking mescaline in 1953 and how he was able to “break on through to the other side” gaining a heightened awareness of reality and a deeper understanding that was not only artistic but sacramental.

He felt that taking psychedelics not only unleashed a kind of madness, but led to a visionary awareness of the sacred.

As were Annie Besant and the Theosophists before him, Huxley was fascinated with the teachings of Krishnamurti. He wrote the introduction for one of Krishnamurti’s books, “First and Last Freedoms.” Huxley, grandson of famous Darwinian scientist Thomas Huxley and author of Brave New World, was notably erudite.

In 1946 while partially blind from his extensive reading he wrote a book called “The Perennial Wisdom” a comparative study of mysticism and compilation of great quotes he had gathered from books on spiritual traditions from China and India to Christianity. By 1954 his position had evolved to the point where he rejected the need for such books. Here’s a short passage from Huxley’s introduction:

This fundamental theme is developed by Krishnamurti in passage after passage. ''There is hope in men, not in society, not in systems, organized religious systems, but in you and in me." Organized religions, with their mediators, their sacred books, their dogmas, their hierarchies and rituals, offer only a false solution to the basic problem. "When you quote the Bhagavad-Gita, or the Bible, or some Chinese Sacred Book, surely you are merely repeating, are you not? And what you are repeating is not the truth. It is a lie, for truth cannot be repeated." A lie can be extended, propounded and repeated, but not truth; and when you repeat truth, it ceases to be truth, and therefore sacred books are unimportant. It is through self-knowledge, not through belief in somebody else's symbols, that a man comes to the eternal reality, in which his being is grounded. Belief in the complete adequacy and superlative value of any given symbol system leads not to liberation, but to history, to more of the same old disasters. "Belief inevitably separates. If you have a belief, or when you seek security in your particular belief, you become separated from those who seek security in some other form of belief. All organized beliefs are based on separation, though they may preach brotherhood." The man who has successfully solved the problem of his relations with the two worlds of data and symbols, is a man who has no beliefs. With regard to the problems of practical life he entertains a series of working hypotheses, which serve his purposes, but are taken no more seriously than any other kind of tool or instrument. With regard to his fellow beings and to the reality in which they are grounded, he has the direct experiences of love and insight. It is to protect himself from beliefs that Krishnamurti has "not read any sacred literature, neither the Bhagavad-Gita nor the Upanishads". The rest of us do not even read sacred literature; we read our favourite newspapers, magazines and detective stories. This means that we approach the crisis of our times, not with love and insight, but "with formulas, with systems" - and pretty poor formulas and systems at that. But "men of good will should not have formulas; for formulas lead, inevitably, only to "blind thinking". Addiction to formulas is almost universal. Inevitably so; for "our system of upbringing is based upon what to think, not on how to think". We are brought up as believing and practising members of some organization - the Communist or the Christian, the Moslem, the Hindu, the Buddhist, the Freudian. Consequently "you respond to the challenge, which is always new, according to an old pattern; and therefore your response has no corresponding validity, newness, freshness. If you respond as a Catholic or a Communist, you are responding - are you not? - according to a patterned thought. Therefore your response has no significance. And has not the Hindu, the Mussulman, the Buddhist, the Christian created this problem? As the new religion is the worship of the State, so the old religion was the worship of an idea." If you respond to a challenge according to the old conditioning, your response will not enable you to understand the new challenge. Therefore what "one has to do, in order to meet the new challenge, is to strip oneself completely, denude oneself entirely of the background and meet the challenge anew."

Those who would with Krishnamurti reject the wisdom of the ancient traditions in light of the soul’s own personal realization would do well to traverse the path of Huxley and first read them.

Those who would with Krishnamurti reject the wisdom of the ancient traditions in light of the soul’s own personal realization would do well to traverse the path of Huxley and first read them.

Perhaps erudite scholars like Huxley have a certain right to cast their books aside in old age and attempt a more direct approach. Krishnamurti’s rejection of books strikes me as too facile a paean to dyslexia. To boast that one has "not read any sacred literature, neither the Bhagavad-Gita nor the Upanishads", is not a qualification. Even dogs and cats could make the same boast if they could talk. The idea, I suppose, is that the truths about life are available to anyone upon introspection. And yet there are many truths that escape us even upon great self-reflection. And self-reflection in our age of distraction is often uncomfortable and sometimes impossible.

Science builds on the achievements of past scientists. The primitive batteries of Volta were the forerunners for the battery in your cell-phone; without access to the accomplishments of past generations of scientists we would be lost. Huxley would never have accepted that modern scientists ridicule and reject the scientific discoveries of his grandfather; why then ridicule and reject the spiritual discoveries of our ancestors?

It may be true that “religion” conditions people socially and that such “conditioning” may have negative effects. But this is not a good reason to reject centuries of research work done by saints and savants who dedicated themselves to self-reflection and spiritual discovery. If generations of scientific discovery are worth preserving that we might better exploit this material world, why not preserve the spiritual discoveries of antiquity to better understand the human spirit?

Krishnamurti wished to discard all the old books. Conveniently, he had not taken the trouble to read them. Are the old books merely sham and mystery? There is paradox in reading the book of a man who did not read books and concluding with him that books are not worth reading or writing.

But are the old spiritual books merely a convenient fraud perpretrated by fools who wish to defy the laws of nature; idiots who scorn science and promote dogma? Are the traditions of the Bible, the Koran, and the Bhagavad-Gita merely the lies and riddles of the weak-minded? Are we to believe that the perennial wisdom of self-realization that flows from ancient times to the present is no more than dogma and eyewash for the general public? Is it really true that these so called “religious” texts are no more than fables and legends to control women and children while the strong devour the weak?

If modern atheists are right and death is final, then it is more courageous to say with Sartre and Camus that life is meaningless and absurd. According to Ann Douglas’ introduction to The Dharma Bums, when Jack Kerouac finally left the road in 1956, he claimed, 'The only thing to do now is to sit alone in a room and get drunk.” Kerouac famously drank himself to death at the age of 47 in 1969. Are we to conclude that the most courageous answer to the paradox of time is to end life with a shotgun blast as did Hemingway? Or with a sword to the entrails as did the fearless Samurai?

Or shall we rather conclude with Tertullian who wrote in 203 AD, “Credo quia absurdum” I believe because it is absurd. Or with Carl Jung who said, “The heavy-handed pedagogic approach that attempts to fit irrational phenomena into a preconceived rational pattern is anathema to me.”

The strident reaction of anti-theists is as harmful to human freedom as the dogma they pretend to oppose. And antitheism with its opposition to certain books often serves a more political end.

People forget, for example, that the post-revolution Soviet communist state carried out a comprehensive “war on religion,” and that even after the revolution the Bolsheviks continued to tear down churches, arrest clergymen, and destroy them in the name of destroying dogma. Atheism took rather savage forms in the Soviet Union in its reaction to the church. While such repression might be unthinkable against the orthodox church today, repression against minority religions is carried out as a consequence of “terrorism laws.”

While “scientists” like Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris rail against religion and its books, it is worthwhile to remember how such campaigns end when taken up by governments.

Communist regimes throughout the 20th century used “scientific” justifications to repress religious faith wherever it became a prominent social force.

And this armed assault on religious faith was aimed not just at Christians—Protestants, Catholics, Eastern Orthodox—but against Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, and other faiths.

In Easter Europe, social movements connected with religious faiths were systematically repressed as “dogmatic.” And For every Cardinal Mindszenty in Hungary, there was a Cardinal Wyszynski in Poland, a Richard Wurmbrand in Romania, a Natan Sharansky or Walter Ciszek in Russia, a Vasyl Velychkovsky or Severian Baranyk or Zenobius Kovalyk in the Ukraine.

In Afghanistan repression led to dire consequences for the Moaddedi. And internationally for followers of the Dalai Lama in China, or for the jailed nun in Cuba who spoke against the Castro regime. During the time of the Khmer Rouge of Pol Pot in Cambodia, Buddhist monks were repressed, forced to renounce their vows, and worked to death in the flooded rice paddies of the Tonle Sap.

The so-called “dogmas” of religion have been repressed by anti-theists wherever free thought and conscience threatened the new regime; whether the despot was Fidel Castro or Pol Pot or Stalin, the sentiment was the same: “Religion is poison,” as Mao Tse-Tung was said to have stated.

From East to West, from Africa to Asia, from Phnom Penh to St. Petersburg, repressive anti-theistic regimes have pursued an all-out assault on religion.

In the 20th century, the Communists may have quibbled over the details of how to implement Marx’s vision, but they were unanimous in one thing: religion was the enemy, a rival to Marxist mind control, and it had to be vanquished regardless of costs and difficulties.

British author Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory documents the post-revolutionary repression practiced against the Catholics in Mexico in the 1930. That repression resulted in the Cristero War, so named for its Catholic combatants' slogan Viva Cristo Rey (long live Christ the King).

The message of the old books is so powerful that whenever it is taken to heart, whenever a social movement grows in strength based on the ancient wisdom it must be repressed, brutally if necessary. I have often heard the meme that “religion is the root of all evil,” or that “religion causes all wars,” but a good case may be made that it is materialism that is the root of all evil. The determination to force people to conform to a materialist way of life has caused much evil in the world as has been seen in the failed systems of communism and the regimes of Mao and of Stalin, of Pol Pot and Fidel Castro. Those revolutionary regimes held science to be the new god as did the bloody followers of Robespierre and Danton during the French Revolution and the age of Terror that followed.

Krishnamurti and company would do away with the old books and their superstitions, having never read them. Modern anti-theists cite the absurdities of the Book of Genesis: “How could the world have been created in seven days?” they say. “The fables of Noah and the Ark or Jonah and the Whale are patently ridiculous. Why not believe in Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy or unicorns and the Great Spaghetti Monster?”

But the old books with all their absurdities and exaggerations help us see through the madness of daily life and the meaninglessness of death. They reveal the experience of spiritual reality that has colored human life since the time of Noah and Jonah and Abraham. They faced great trials and were guided by their faith as were the Rishis of the Bhagavat who penned their visions of divine wisdom on palm leaves thousands of years ago.

How do we confront the mystery of death if not with the mystery of faith? Without faith there is only paralysis. Without faith there is only hopelessness. We need the anaesthesia of the bottle or the needle to help us make it through another day.

The mythic stories of the Bible and Puranas are not mere lies and riddles. They help us strike deep at higher truths; they strike a harmonic chord deep in the human soul that understands intuitively the nature of the eternal soul and the power of divinity. The sound of that chord cannot be silenced or stopped. The old creed has survived the whips and scorns of anti-theistic critics over generations because it reveals the self-reflection and realization of thousands of advanced sages over milennia.

The ancient wisdom of the Puranic and Upanishadic wisdom has survived the onslaught of Muslim conquest and British colonization in India and has spread to the west through the teachings of Thoreau and Emerson, of Schopenhauer and Schlegel, and even the quantum realities of Schrodinger and Oppenheimer. While these books were ridiculed by Christian missionaries as the crude fables of black Hindooo tribesmen, the old books survived on the basis not only of their deep wisdom and insight but their supple and flexible handling of the problem of human mortality, the transcendental reality of time, and the eternal relationship between soul and Deity.

While Krishnamurti and his fans offer us nothing more than empty introspection in the face of an absurd and meaningless reality, the ancient Bhagavat has the nature of an Oracle. The Oracle reveals truth; but the truth has many meanings and interpretations. Every time we consult the Oracle we find a new idea, a new sense. The text remains the same, but oddly reveals new light every time it is consulted. Self-reflection is often a stagnant, futile exercise. Every time I look into myself I find the same qualities of fear, selfishness, lust, anger and greed.

But the Oracle reveals other qualities: faith, surrender, devotion, toleration, and selflessness. Where self-reflection is often opaque and reveals nothing more than my own limitations; The Oracle teaches there is something higher. In a world of infinite gradations, where is the infinite? The Oracle gives us a hint. The Bhagavat is an oracular text spoken by oracles like Suta, Shukadev, Vyasa and Narada. It is filled with revelations from Kapila, from Maitryea, from Vidura and Uddhava. The stories of the Bhagavat give us insight into the character and vision of these great saints and oracles. Each time we read the Bhagavat we find a newer and deeper meaning. This is why the old books are there. They respond to our questions. They are living texts, unlike the book of our own life which is limited and marked by our own limited memories and imagination.

The Greek Heraclitus pointed that it is impossible to set foot in the same river twice. The current has changed. The water has changed. Even the river bed itself has subtly shifted. We ourselves are changed from the version of self we knew only a few moments ago, for now we have the memory of the river and its water. Now it is slightly colder or warmer. The same river is never the same river twice. In this way the text of the Holy Bhagavat reveals something new every time we approach it, for we have changed, our world has changed, our body has changed.

It has been said that mythology is really someone else’s religion. But mythological texts survive, not because of their fables and tales but because of their universal truths. As young men we read the Iliad and thrill to the heroism of the Greeks and Trojans. As mature men we find the angry pouting of Achilles repellant. He seems to be more of a cry-baby than a hero. Why not confront the challenge? He is a coward who refuses the call of adventure with tragic results. As older men we understand the anger and reluctance of Achilles and pity him his shortcomings while recognizing his true heroism. He overcomes his petty sentiments and gives his life while submitting to his karma.

In the same way, we first read the happy stories of Krishna as children and find entertaining bed-time stories. We read the Bhagavat in the full bloom of youth and look for a message about love. Later we read the Bhagavat in our maturity and consult the Oracle for news of what happens beyond our death and discover our real eternal prospect through faith.

Our understanding changes as we grow and develop Our penetration in to such deep works of faith--our capacity to interpret their meaning-- is always tempered by our own expectations, regrets and short-comings as we approach the text. So it is that the text itself never changes--its meaning is always literal--but our own version and interpretation must change even as we change. It is for this reason that the old texts, the ancient Puranas, and especially the Bhagavat continue to have a living meaning--even for a highly technological society with a deep dependence on technology and the logic-driven algorithms that drive our daily life.

But even personal consultation with the oracular literature of the Bhagavat may not provide us with the peace that surpasses understanding. In the end, we must consult an adept whose faith is deeper than our own. Our own personal understanding of the book Bhagavat is enhanced by the person Bhagavat who explains with both precept and example the inner sense of the oracle.