Greed

By Michael Dolan/B.V. Mahāyogi

Greed and desire has led many a man to his demise.

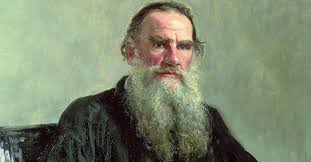

The old story by Tolstoy is instructive. A peasant, determined to increase his fortune, hears that land is cheap in the East. He travels far from home where he finds vast plains of black farm-land presided over by a strange band of gypsies. Their warlord charges a special rate for land: One may have as much land as he can cross on foot in a day, measured from sunrise to sundown.

He pays his entire fortune for a day's worth of land. The money is placed in a sailor's cap, marking the starting point. The warlord sits on a camp stool to watch. They wait for the sunrise to begin.

At the first glint of sunrise the peasant begins to pace off his land. At first he walks quickly, then, overcome with greed, he runs to the horizon, covering as much land as he can. He turns at noon, calculating the far corner. Running and running, his chest bursting, he makes the far corner by late afternoon. Now he must sprint back to the starting point.

The sun is low. It is setting. The peasant, exhausted now, thirsting for a drop of water, runs as fast as he his legs can carry him, staggering back to the spot where the warlord sits, laughing. As the sun dips below the horizon, the peasant drops dead a few feet from the starting spot. The warlord scoops up the sailor's cap from the ground before the peasant, pockets the money, and puts the cap back on his head. He pauses for a moment over the fallen peasant and gives instructions to his men to bury him. He will need a piece of land six feet long, three feet wide and ten feet deep.

The story is called, "How Much Land does a Man Need?" and the final line gives the answer: as much land as is necessary for burial.

In illustrating a point he had made about how greed destroys a man’s soul, Śrīla Śrīdhara Mahārāja once told me the story of a man who had drowned trying to save a bar of gold. During a flood, he packed his worldly goods and his fortune in gold on a boat and tried to cross the Ganges in a storm.

|

| Shipwreck |

His boat too was flooded. He began to sink. He filled his pockets with the gold and began to swim. The weight of the gold took him to a watery grave.

I was always struck by the image of a man filling his pockets with gold and trying to cross the Ganges. Śrīdhar Mahārāja often used examples drawn from a number of sources to illustrate his lectures. As editor of his printed works, I was responsible for filling in some of the details and running down the origin of some of his stories.

After many years of reflecting on the story of the drowning man with gold in his pockets, the other day I found a version of it in an essay by John Ruskin.

The story, of course, was not original with the discourse of my Guru Maharaja; it had probably been gleaned from a book written by Gandhi, a translation of John Ruskin’s Unto this Last. Śrīdhar Mahārāja may have read the Gandhi version of Ruskin or may have heard the story told in Gandhian circles in the early days of the mission. Certainly the Indian Independence Movement was prominent in Bengal during the early part of the 20th Century, and Śrīdhar Mahārāja may have heard the story in his conversations at the time.

Whether Śrīdhar Mahārāja was familiar with Gandhi’s or Ruskin’s version is immaterial. The point of the story is that greed and material attachments may cause us to lose our spiritual compass. I will take the image of the drowning man trying to swim with gold in his pockets to my grave.

Gandhi often preached on the vicissitudes of greed. He sincerely felt that a system based on exploitation and greed, i.e. capitalism was doomed to inevitable failure.

In a chapter in his Autobiography (Part IV, Chapter XVIII) entitled ‘The Magic Spell of a Book’ Gandhi tells us how he formed his views on capitalism and greed while reading John Ruskin’s Unto This Last on the twenty-four hours’ journey from Johannesburg to Durban. It made such an impression on him that he was struck by insomnia.

‘The train reached there in the evening. I could not get any sleep that night. I determined to change my life in accordance with the ideals of the book.…I translated it later into Gujarati, entitling it Sarvodaya.’

Gandhi was far more sophisticated than he appeared to be. Far from being the “half-naked” fakir of Winston Churchill’s fertile imagination Gandhi was quite well-read. Having been educated as a barrister before becoming a human-right’s advocate in South Africa he wore tails and a top-hat to work long before he adopted simple hand-weaved cotton cloth.

The story about “How much land does a man need?” fits nicely into the Gandhian point of view, a view that deeply influenced Gandhi. Since we began this article with a reference to Tolstoy, it is also interesting to note the relationship between Gandhi’s ideas and Tolstoy. Gandhi was hypnotized by Tolstoy’s later writings, especially his pacifist criticism of Church and State: The Kingdom of God is Within You. Gandhi went so far as to found a communal farm along Tolstoyan principles in South Africa. He admired and corresponded with Tolstoy whose ideas were later incorporated into the Independence Movement as nonviolent or passive resistance.

As he saw abuses against human rights in India and South Africa, Gandhi found solace in the writings of Ruskin and Tolstoy and was drawn to a life of simple living and high thinking. Ruskin’s critique of capitalism and Tolstoy’s principles had such an effect on him that he set up a farm at Phoenix near Durban where he and his friends could follow those “experiments in truth.” Later he founded “Tolstoy Farm” near Johannesburg; the basis for his more famous ashrams in India, at Sabarmati near Ahmedabad.

Gandhi found that greed is a destructive principle. If capitalism is based on greed, it must ultimately fail.

To get back to Śrīdhar Mahārāja’s cautionary tale of the man who tried to cross the Ganges with gold in his pockets, John Ruskin’s version involves a tale is told of a California miner whose fortune is in gold bars. He’s trapped on a wrecked steamboat on the Sacramento River. As the ship goes down, the passengers help him with his gold:

“I can still hear him shouting at me:

Lately in a wreck of a Californian ship, one of the passengers fastened a belt about him with two hundred pounds of gold in it, with which he was found afterwards at the bottom. Now, as he was sinking--had he the gold? Or the gold him?”

The title of Ruskin's essay, "Unto this Last" derives its title from the Parable of the Workers in the Vineyard:

I will give unto this last, even as unto thee. Is it not lawful for me to do what I will with mine own? Is thine eye evil, because I am good? So the last shall be first, and the first last: for many be called, but few chosen.

The title of Ruskin's essay, "Unto this Last" derives its title from the Parable of the Workers in the Vineyard:

I will give unto this last, even as unto thee. Is it not lawful for me to do what I will with mine own? Is thine eye evil, because I am good? So the last shall be first, and the first last: for many be called, but few chosen.

— Matthew 20 (King James Version)

John Ruskin, Unto this Last https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unto_This_Last

You can read Ruskin’s entire essay here: http://dbanach.com/ruskin.html

For more information on John Ruskin: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Ruskin

|

| John Ruskin painted by the Pre-Raphaelite artist John Everett Millais standing at Glenfinlas, Scotland, (1853–54). |

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.