Consciencia y Ser IX

Dios, Demonios y los Planetas Sombra

Pregunta acerca de las maravillas del mundo

y escucharás acerca de la Gran Pirámide de Egipto, las ruinas misteriosas de

Machu Picchu en Perú; la Gran Muralla China, la Pirámide de Kukulcán en Chichen

Itza en Yucatán, México. El Coliseo Romano, el Taj Mahal en Agara, India e

incluso el Palacio de Invierno de los Zares de Rusia, ahora el Museo del

Hermitage en San Petersburgo, Rusia también deben mencionarse, junto con el

Louvre de Parías, o el Palacio de Versalles, residencia de los últimos reyes de

Francia.

Ninguno de estos se compara en esplendor y

misterio al Angor Wat. Angor Wat, la “ciudad que es un templo! Es el más

imponente de los templos de montaña construido durante el apogeo de la civilización

Khmer. Para consagrar el culto a Viṣṇu y el rey que construyo Su monumento,

Suryavarman VII.

En los valles del lago Tonle Sap en

Camboya, artesanos y arquitectos de la antigua Khemer trabajaron sin parar para

concluir el gran templo de Viṣṇu en Angkor durante la vida de Suryavarman. La

calidad de su diseño y los adornos de piedra tallada, la simbolización del

Monte Meru como el centro del universo Védico, Sus santuarios y su santuario

interior, y sus espejos de agua hacen de Angkor Wat un espacio espiritual único

sin paralelo en su arquitectura.

En sus escritos de 1585, el explorador

portugués Diego De Couto antoa, “Este tempo es una construcción tan particular

que uno difícilmente puede describirla con la pluma, no puede uno compararlo

con ningún otro edificio del mundo”. Cientos de años después, su descripción

continúa vigente.

En algunas secciones del edificio cada

pulgada cuadrada del techo ha sido labrada a mano con intrincados diseños.

Mientras que el complejo de templos en Camboya abarca cientos de millas

cuadradas, Angkor Wat se halla por encima de estas como el templo más

importante de todo el Khmer. Aquí los edificios están construidos con la idea

de replicar el mítico Monte Meru, considerado como el centro del universo.

En un sentido, Angkor Wat es un yantra, una

especie de máquina arquitectónica hecha para conducir a sus visitantes hacia la

consciencia elevada a través de un complejo mandala de espejos de agua,

santuarios, bajorrelieves y oratorios interiores. Ningún visitante se va sin

que su consciencia haya sido tocada por la experiencia meditativa profunda. Es

el complejo religioso más grande construido por el hombre.

Si como Le Corbusier dice, “Una casa es una

máquina para vivir”, entonces Angkor es una máquina para elevar la consciencia

y desarrollar la consciencia divina. Construida en una era en la que pocos

tenían acceso a los libros y menos aún eran capaces de leer y escribir, Angkor

no sólo cuenta una historia mientras uno camina atravesando sus salones: es una

mecanismo especial para traerlo a uno hacia un nivel de consciencia más elevado

no sólo a través de la contemplación de sus maravillas arquitectónicas, sino

también a través de la manipulación del espacio meditativo. Y mientras uno vaga

a través de este espacio meditativo, tras cruzar el foso que separa el espacio

interior de Angkor del mundo exterior de las empolvadas calles de Camboya, en

donde uno es golpeado por el poder de las puertas exteriores y las torres.

Adentrándose un poco más, uno llega uno a un salón de enormes bajorrelieves de

paredes laterales talladas hace cerca de 800 años por el mejor escultor de

Suryavarman VII.

Entre los intrincados relieves está la

historia del Ramāyana y el Mahābharata, que se hace visible para todos aquellos

que han escuchado estas epopeyas y quienes la conocen de memoria pero que eran

incapaces de leer el sánscrito. En las Galerías Orientales está un enorme

bajorrelieve ue cubre toda la pared: ahí están Rāma y Lakṣmana y Hanumāna, el

Rāvaṇa de las diez cabezas y su hermano Vibhiṣana, Jambhavan el oso y sus

ejércitos. Del otro lado está el Mahābharata con Bhīma y Arjuna, Yudhiṣthira y

sus hermanos, los mil soldados de la guerra de Kurukṣetra encabezados por Bhiṣma.

Están los carros de guerra y Bhiṣma empalado en flechas.

Teniendo en cuenta los límites del espacio

de la pared, uno se pregunta a qué historias del mundo antiguo se le estará

dando prominencia aquí. Al continuar caminando uno alcanza la galería este,

Aquí uno se enfrenta a otro enorme bajorrelieve. Una inmensa talla de piedra de

la historia del batido del océano de leche.

Se relata esta historia en el Mahābharata y

en los Puranas, notablemente en el Bhāgavat Purana. Es una especie de historia

de la creación. De hace mucho tiempo, antes de que el mundo empezara, los

dioses o suryas eran amenazados por los danavas los demoniacos opositores de

dios. Cuando ellos le pidieron ayuda a Viṣṇu, el Señor del Universo, explicó

que necesitarían el amrta, una especie de tónico para la inmortalidad. Este

amrita lo podrían hallar en el fondo del océano de leche, pero los dioses

tendrían que batir el océano para alcanzarlo. Los dioses usaron la a Mandara,

la montaña mística como batidor y envolvieron a la serpiente Vasuki a su

alrededor como su soga.

Los demonios anti-dios se reunieron ahí,

estimulados por la idea de que iban a tomar ellos mismos el néctar. Los dioses

tomaron a la serpiente por la cola y los demonios por la cabeza y empezaron a

batir la montaña. Cuando a hundirse, Viṣṇu, encarnado como la tortuga cósmica

sostuvo el batidor, la montaña Mandara, en su espalda. Y así los dioses y

demonios empezaron a batir el océano de leche.

Poco a poco, seres extraños y maravillosos

emergieron de esa sopa: el caballo de siete cabezas Uchaishravas, la diosa

Lakshmi, junto con las apsaras celestiales, ninfas celestiales divinas. Ahí

apareció Surabhi la vaca de los deseos junto con la mismísima luna y la joya

kaustabha que adorna el pecho del Señor Viṣṇu. Muchas hierbas valiosas,

medicinas fueron producidas por el batido, también algunos venenos aparecieron.

Esta miasma era peligrosa así que fue sorbida por el Señor Śiva quien la

contuvo en su garganta, la cual se tiñó de azul. Por esta razón es llamado,

“nila-kanta” o el de la garganta azul.

Cuando finalmente surgió el amrita en la

superficie fue recogida en una vasija dorada, por el médico entre los dioses,

el mismísimo Dhanvantari, otra forma de Viṣṇu. Los demonios se apresuraron a

tomar la vasija y robar el néctar de la inmortalidad de los dioses.

Pero de nuevo Viṣṇu encarnado, ahora como

una hermosa joven con una sonrisa encantadora y con los labios rojo rubí,

Mohini. Disfrazado como la encantadora Ninfa, el mismísimo Dios Viṣṇu convenció

a los demonios para que esperaran su turno mientras el néctar era distribuido

primero a los dioses. Distraídos por la belleza, los demonios se sentaron y

vieron como se entregaba hasta la última gota a los sedientos dioses, quienes

se hicieron inmortales al beber ese néctar.

Todos excepto Rāhu, Este inteligente

anti-dios se sentó entre el sol y la luna y se las arregló para obtener una

probada del néctar. Pero antes de poder tragarla, fue detectado por el propio Viṣṇu

quien de inmediato desenfundó su arma sudharshana chakra y decapitó al demonio.

Y sin embargo, puesto que el néctar había tocado los labios y garganta de Rāhu,

su cabeza se hizo inmortal. Para asegurarse de que no hiciera daño fue arrojada

hacia los cielos. Ahí se sitúa hoy como una especie de planeta de sombra. De

acuerdo con la tradición Hindú, el eclipse de sol es causado debido a que Rāhu

intenta comerse al sol. Pero ya que no tiene cuerpo, el sol pasa rápidamente a

través de su garganta.

En la astrología Védica, la influencia de Rāhu

se calcula en el horóscopo de uno. Ya que Rāhu es un “planeta sombra” y no

existe físicamente, aun así su impacto es considerado importante., lleno de

fuerza y significado divino. Con su naturaleza sombría, Rāhu actúa en el nivel

emocional e interno.

Una lectura superficial de esta historia

produce nada más una especie de mito, una explicación extraña sobrenatural del

universo que poco tiene que ver con nuestra experiencia.

Y sin embargo, cuando vi el bajorrelieve en

Angkor no podía sino preguntarme el porqué de que esta historia en particular

tenía un sitio de honor para Suryavarman VII. Por qué sus escultores expertos

llegaban a tales extremos para inscribir para siempre este suceso en las

paredes de piedra del templo. Debe tener un profundo significado, más allá de

lo mero superficial de la creación de la historia. De hecho, lo tiene, como

podremos ver. Su explicación se expande en el tema que hemos estado explorando,

acerca de la veracidad de la versión Védica, junto con el ser y la consciencia,

particularmente el significado de cidābhāsa, o de la consciencia “confusa a

través de la cual la mente tiene que pasar para llegar a la materia”.

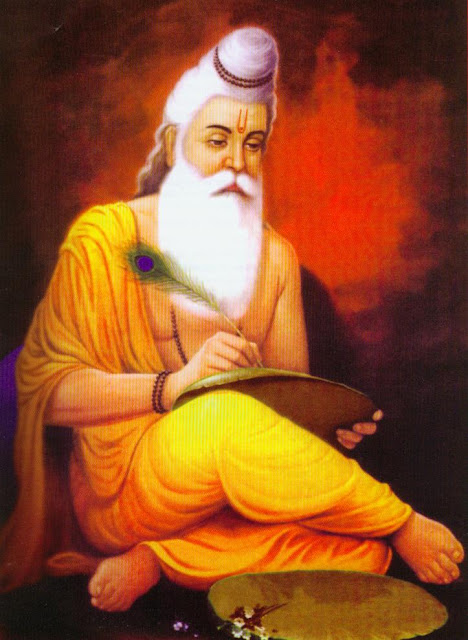

Sridhar Mahārāj comenta acerca de este

tópico y el significado de Rāhu en su libro, “Evolución Subjetiva de la

Consciencia”.

“En una ocasión, consideré desde este punto

de vista la pregunta de los planetas en la cosmología Védica. Podemos ver que a

través del movimiento de los distintos planetas, un eclipse solar es causado

por la sombra de la luna que cae sobre la Tierra. Y sin embargo en las

escrituras se ha descrito que durante un eclipse, el planeta Rāhu devora el sol

o la luna. Cuando Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura estuvo en Purī

durante sus últimos días y llegó un eclipse, un devoto que se suponía conocía

el Siddhānta, la conclusión de las escrituras, estaba sentado junto a

Prabhupāda, De pronto ridiculizó la idea dada en el Bhāgavatam que durante el

eclipse solar o lunar Rāhu devota al sol o la luna.

Yo no pude tolerar que tal observación se

admitiera en referencia al Bhāgavatam y argumenté que lo que declaraba el

Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam no se ha de tomar a la ligera. Ofrecí lo que parecía ser un

poco de apoyo descabellado. Y dije que Bhaktivinod Ṭhākura había creado muchos

personajes, pero yo pensaba que estos no eran imaginarios.

Lo que él había escrito podía haber

ocurrido durante algún otro milenio (kalpa), o día de Brahmam y que ahora se

tomaba a la ligera, Considerando la importancia del significado literal de las

escrituras, Bhaktivedānta Swāmi Maharaja presento su Bhagavad-Gita tal como es.

“Yo pensé ‘¿Cómo puedo probar lo que dice

el Bhāgavatam’ no lo sé. Pero lo que se ha dicho en el Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam ha de

ser cierto. Yo tengo fe en ello.

“Hay tantas declaraciones acerca de la

cosmología del universo en las escrituras, Los Aryans, los hombres

desarrollados espiritualmente de tiempos pasados, solían verlo todo como

consciencia. Ellos vieron que la sombra también es consciencia.

“La sombra, abhāsa, también es considerada

un estado de consciencia. Únicamente a

través de esa etapa sombría de consciencia podemos llegar a la concepción

material de las cosas. Antes de alcanzar la concepción de una sombra, tenemos

que pasar por un estado mental, y la personificación puede estar ligada a un

estado mental. La personificación de la sombra puede denominarse como “Rāhu”.

El alma se aproxima a la materia, le mundo

material, pero antes de eso, ha de pasar a través de un estado de consciencia

sombrío llamado cidābhāsa.

“La consciencia pasa a través del nivel de

consciencia de la sombra hacia la materia, no consciente. Y ese etapa sombra de

consciencia tiene su personalidad. Es también consciente, y puede ser conocido”

ver las cosas como materiales. Lo que es materia concreta es desconocido. Es un

mero efecto de la consciencia. Como todo lo material ha de tener algún origen

consciente, u origen en la consciencia personal, ha de haber una concepción

personal del sol, la luna, la Tierra y también de los planetas. Antes de

alcanzar la concepción de la sombra de algún objeto, el alma ha de pasar a

través de un estado de consciencia. Ese estado tiene alguna existencia

espiritual como persona.

Por ello el Bhāgavatam hacer referencia al

sol, la luna y el planeta Rāhu, como personas. Todo, la Tierra, la luna, las

estrellas, los planetas. Tienen una concepción personal. En el fondo de lo que

podemos percibir con nuestros sentidos embotados, todo lo que se dice que es

material, ha de tener una concepción personal. Sin la influencia de una

concepción personal, la consciencia no puede alcanzar la etapa de materia

burda.

Por lo tanto, en las antiguas escrituras,

hallamos que los grandes sabios y rsis siempre se refieren a todo en este mundo

como a una persona. Aunque para nosotros es materia inerte, ellos la

consideraron como personas ¿Por qué? La materia no es sino sombra de la entidad

personal. Lo personal. La entidad consciente es más real.

Cuando concebimos la representación

personal de esa sombra, se le conocerá como Rāhu. Todo es consciente. La

sombra, su efecto-todo. Cuando la luna se halla entre el sol y la tierra, la

sombra de la luna llega aquí, y lo que llega también es consciente. Todo es

consciente en un principio, luego está la materia. De la concepción personal

evolucionan las cosas hacia la consciencia burda. Todo esto es personal.

Entonces los ṛṣis con esa visión de la realidad solían designar todo como

personal: los árboles, las montañas, el sol, la luna, el océano. Cuando la

consciencia pura llega a experimentar la materia pura, entonces debe primero

que tener una etapa de mezcla, y eso es una persona que sufre en el karma.

Persona significa que no están totalmente desarrolladas completamente en el

presente como personas espirituales, sino en una condición mezclada. Así que lo

que los rsis están diciendo. Que todo es una persona- es real, no es un

mejunje.

Todo es consciente. Tal como los

científicos actuales dicen que todo es materia, tenemos verdaderas razones para

pensar que todo es consciente. Todo lo que ves no importa, podemos sentir

directamente lo que hay en nuestra propia naturaleza. Eso es consciente.

Nuestra consciencia puede estar en una posición desarrollada o degradada, pero

la consciencia se halla cerca de nosotros. Sentimos únicamente nuestra energía mental”.

“Todo tiene su representación en la

original, personal, consciente, realidad espiritual. De otro modo no sería

posible que se reflejara en este plano como materia. Primero hay consciencia y

luego cuando se halla en una condición más burda, aparenta ser materia. En el

estudio de la ontología se enseña que cuando estudiamos algo en particular, a

pesar de que podemos saber que tiene ciertos atributoa a la vista, y que

aparece al oído de cierta manera, que todo esto son apariencias.

Independientemente de las apariencias, el aspecto ontológico de una cosa- lo

que es- la realidad de algo- es desconocida e incognoscible.

“Mi opinión es que cuando la consciencia va

a sentir la materia no consciente tendrá que pasar a través de un área de

consciencia para encontrarse con el objeto material. Para que la percepción

completa de esa cosa material no pueda ser sino consciente. Y consciencia

siempre indica persona. Primero está la concepción y después la idea material.

El mundo consciente está muy cercano y el

mundo material está muy lejano, Por ello los grandes rsis, cuyo pensamiento

estaba altamente desarrollado, se dirigían hacia todo lo que hallaban en el

ambiente como si todos ellos fueran personas. En los Vedas, la antiguas

escrituras de India, hallamos que los santos y los sabios siempre están en

medio de tantas personas; en el fondo todo es una persona”.

“Pensando, sintiendo, deseando- una entidad

viviente tiene tres fases. Y es lo mismo también con Dios y sus potencias.

Primero hay un sujeto que existe, luego sus experiencias. Y las experiencias

del carácter sutil son lo primero y se les da la mayor importancia. Y cuando el

sujeto llega a un área más lejana para concebir la materia, ese será para él el

punto más alejado. Se dirigirá a todo lo que le rodea con sus concepciones

personales.

Una concepción personal no puede sino

señalar que la materia está lejana. La conexión directa de la consciencia es

con la sombra, el reflejo de la materia hacia el mundo consciente. El alma

puede entender únicamente eso. Si la materia puede existir independientemente,

entonces también la materia tiene una sombra en el mundo consciente y el alma

tiene que ver con esa sombra.

En otras palabras. Existe la persona y

entonces el cuerpo. Tal como el cuerpo es el efecto posterior del agente vivo

consciente, la materia es el efecto posterior del espíritu., Independientemente

de toda la consciencia material, todo lo que está en contacto con el alma es

totalmente personal.

Cidābhāsa es algo como la substancia mental

que tenemos en el interior. Hay dos clases de personas kṣara y akṣara: el alma

pura liberada y el alma que lucha en la materia. Cuando las personas liberadas

y no liberadas se mezclan en el mundo de las transacciones materiales. Ya sean

entidades móviles o inmóviles o sea cual sea su posición, aun así han de ser

consideradas personas. Debido a que todo es una unidad de consciencia, todo

tiene una existencia personal. “Todo es una persona. Antes de ir hacia la

concepción material, hemos de pasar a través de una concepción personal o

aspecto de esa cosa. En Vṛndāvana todo es consciente, pero algunas cosas posan

en forma pasiva. Pero todas ellas son conscientes: el río Yamunā, las vacas,

los árboles, los frutos-todo es consciente, espiritual, pero ellos posan en

diferentes formas. Los Aryans, siendo capaces de detectar las características

conscientes de todo, ven toda la naturaleza como consciente y personal y se

dirigen a todo como consciente.

La consciencia y personalidad son las bases

universales de la realidad. Cualquier cosa que experimentamos es consciente. El

reflejo de un objeto material se halla en mí y el plano en mi interior es

consciente. El sujeto es consciencia, y cualquier clase de cosa que pueda ser

el objeto, proyectará su reflejo hacia el plano de consciencia. El observador

de cualquier realidad objetiva se envuelve sólo con la consciencia de principio

a fin y no puede tener ninguna concepción de materia aparte de la de la

consciencia”.