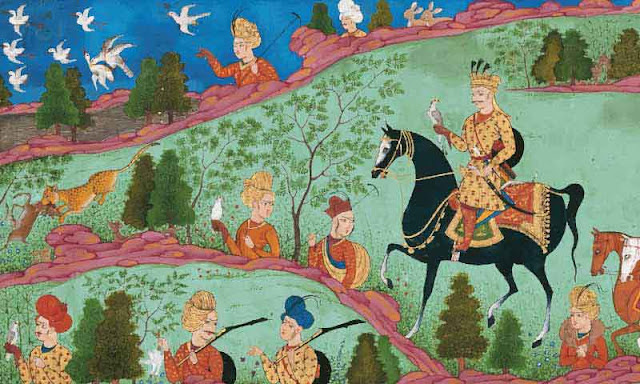

Purush y Prakriti: Masculino y Femenino,

dios and diosa.

नारायणं नमस्कृत्य नरं चैव नरोत्तमम्

देवीं सरस्वतीं चैव ततो जयम् उदीरयेत्

महाभारत

Mahābhārata

Una version de

Michael Dolan, B.V. Mahāyogī

Bhagavad-Gītā Capítulo 13 continuación.

Cuando Arjuna le pregunta a Kṛṣṇa acerca de

prakṛti y puruṣa, hace una pregunta filosófica profunda que llega hasta el

corazón de la realidad.

Puruṣa y Prakṛti:

Sujeto y Objeto

Vemos la palabra Puruṣa en Sánscrito desde

el punto de vista del “sujeto,” en donde Puruṣa significa “sujeto” y prakṛti

significa “objeto,” y concluye con el argumento de Śrīdhara Mahārāja que el

sujeto determina al objeto, eso es que la palabra subjetiva, o “consciencia” es

responsable de lo objetivo o del mundo percibido. Sin la percepción del sujeto

el así llamado mundo “objetivo” no tiene una existencia verdadera.

Este es el concepto básico del idealismo.

Pero Śrīdhara Mahārāja, y de hecho el propio Kṛṣṇa toma el argumento un paso

más allá. Sin la percepción de parte del Súper-sujeto, el así llamado mundo

“objetivo” no tiene realidad. El mundo es real entonces, pero es real a causa

de la percepción como tal del propio Dios en la forma de Súper Sujeto, o Paramātmā. Śrīdhara Mahārāja se

refiere a esto como Realismo Ideal. Encuentra un terreno común entre los puntos

de la filosofía Vedanta y el razonamiento de Berkeley y Hegel.

La idea de que el mundo es irreal se ve en

oposición a los comentaristas Vedánticos. Los seguidores de Śaṅkarācārya se

conocen como “Mayavadis” porque apoyan la opinión de que mientras el Brahmán o

espíritu es real, el mundo es irreal, siendo sólo una ilusión. (brahma satyam,

jagan mithya).

Ya que argumentan por la unidad, la

evidente dualidad de la existencia es difícil de explicar. Si todo es uno,

¿cómo es posible que la materia exista junto con el espíritu? Su teoría de

“ilusión” se supone que reconcilia esto. Pero es difícil de explicar cómo la

realidad de lo espiritual absoluto se pervierte hacia la irrealidad del mundo

material “ilusorio.”

Los seguidores de Sri Caitanya consideran

este análisis inexacto. El mundo es real. Su realidad es temporal. La dualidad

existe. No somos “uno” con el absoluto. Compartimos ciertas cualidades: tal

como un rayo de sol comparte las cualidades ultravioletas con el sol radiante,

así el alma individual o jīva comparte las cualidades de sat cit y ananda con

la Consciencia Suprema.

Pero hay una gran diferencia en grado: Katha Upanishad

dice, nityo nityanam cetanas cetananam eko bahunam yo vidadhati kaman: “Entre

los seres eternos conscientes, hay un primer eterno entre todos los eternos. Él

es la entidad suprema viviente de todas las entidades vivientes, Y sólo Él es

el sustentador de toda vida.” La distinción entre las palabras física y

metafísica es real pero inconcebible (acintya-bheda, abheda tattva) por encima

de nuestra capacidad cognitiva.

Esto es para decir que tanto la dualidad

como la no dualidad son reales y coexisten, pero por encima de la capacidad de

la razón. El filósofo alemán Kant estableció los límites de la razón, y sin

embargo creía que había una experiencia trascendental más allá de la razón.

Si contemplas una ilusión óptica veras

movimiento en donde no lo hay. Cognitivamente tu sabes que ahí no hay

movimiento, pero tus ojos te dirán que los círculos se mueven.

Así la naturaleza de puruṣa y prakṛti al

igual que la distinción entre los dos es real pero inconcebible. A la Realidad

Divina sólo es posible aproximarse a través de la fe. La fe, como un

instrumento por encima de lo cognitivo, puede guiarnos en la realización de la

naturaleza verdadera de la consciencia y nuestra relación con el absoluto.

Palabras como “sujeto” y “objeto” tienen un

tono filosófico seco. La concepción de puruṣa y prakṛti tal vez se pueden

entender más fácilmente si consideramos

el significado de puruṣa como “predominante” y el de prakṛti como

“predominado.”

El “Principio de Diosa”

De hecho, el traductor de Śrīdhara Maharāja

ha titulado el 13º capítulo “El Predominado y el Predominante,” el Sánscrito,

prakṛti-puruṣa-viveka-yoga प्रकृति-पुरुष-बिबेक य़ोग El título de este capítulo

significa que el verdadero punto a discutir es la naturaleza de puruṣa y prakṛti.

Dejando de lado “Sujeto” y “Objeto,” o “Espíritu” y “Materia” como posibles

términos vagos, las palabras puruṣa y prakṛti también pueden definirse como “El

Disfrutador, y el Disfrutado,” “El Predominante y el Predominado.”

En un

esquema mayor de la realidad, Dios Mismo es Puruṣa, la Persona Suprema, el

Disfrutador, La Realidad es por sí misma y Para sí misma y existe sólo para Su

placer. Prakṛti entonces es lo que es “disfrutado” por Él. Sexualmente hablando

Prakṛti es femenino, mientras que Puruṣa es masculino. Los aspectos positivo y

negativo de la divinidad implican tanto dios como diosa. Tanto así, Laksmi

puede considerarse como el Prakṛti de Viṣṇu por ejemplo.

Otro

ejemplo del principio dios-diosa son Shiva-Parvati, en donde Shiva representa

la energía colectiva espiritual y Parvati la energía material receptiva cuya

combinación da lugar a la evolución de la existencia materialista.

El

Shiva-Lingam es la representación de sus aspectos pro-generativos combinados:

en donde el poder espiritual productivo se encuentra con la energía material

femenina receptiva.

La

Energía Femenina Divina se complementa con la Energía Masculina Divina como

Mitades Predominante y Predominada de la Misma Verdad Absoluta, de acuerdo con

la escuela Caitanya Saraswata del Vaisnavismo, como se ve en la Deidad de Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa.

Cuando

la entidad viviente se identifica a sí mismo erróneamente como el “Disfrutador”

la naturaleza material actúa como el “Disfrutado.” En realidad todas las

entidades vivientes son “objetos” o prakṛti de la Persona Suprema (Puruṣa) el

Súper Sujeto. Cuando un alma individual se apropia indebidamente del papel de

puruṣa, a través del ego falso, intenta disfrutar la naturaleza material

concebida erróneamente y llamada prakṛti.

Cuando

esta situación se corrige a través de la auto-realización, el alma individual

llamada Jīva regresa a su posición constitucional de prakṛti. En un sentido

filosófico estricto, la Jīva (alma) es considerada como femenina, de naturaleza

predominada, en contraposición con la naturaleza del masculino predominante del

Absoluto Supremo.

Como

una forma de rodear los aspectos sexuales de la concepción positiva y negativa

con el uso de las palabras puruṣa y prakṛti, en donde el masculino es positivo

y el femenino negativo, otra terminología se usa aquí, esa es kṣetra and kṣetrajna.

Teoría

del Campo

kṣetra

significa “campo.” Aquí el Bhagavad-Gīta retoma la cuestión de la “teoría del

campo.” El “campo” macro-cósmico es el continuum espacio-tiempo, de dimensiones

vastas pero finitas, universo cuya órbita elíptica describe un huevo o aṇḍa.

El

conocedor del campo es llamado kṣetrajña. Este término se refiere tanto al conocedor subjetivo, el quantum

infinitesimal conocido como Jīva, al igual que al conocedor súper-subjetivo, el

Paramātmā infinito.

En su

explicación de la “teoría del campo” o de consciencia establecida en el 13º

Capítulo del Bhagavad-Gīta, Bhaktivedānta Swāmi comenta:

“Arjuna

inquirió acerca de prakṛti, o naturaleza, puruṣa, el disfrutador, kṣetra, el

campo, kṣetrajña, su conocedor, y del conocimiento y del objeto del

conocimiento. Cuando inquiere acerca de todo esto, Kṛṣṇa dice que este cuerpo

es llamado el campo y que quien conoce este cuerpo es llamado el conocedor del

campo. Este cuerpo es el campo de actividad del alma condicionada. El alma

condicionada está atrapada en la existencia material, e intenta enseñorearse

sobre la naturaleza material.

Y

entonces, de acuerdo a su capacidad de dominio de la naturaleza material,

obtiene un campo de actividad. Ese campo de actividad es el cuerpo.

Y ¿qué

es el cuerpo? El cuerpo está hecho de sentidos. El alma condicionada quiere

disfrutar de la gratificación de los sentidos, y, de acuerdo a su capacidad de

disfrute de la gratificación de los sentidos, se le otorga un cuerpo, o campo

de actividad. Por ello el cuerpo es llamado kṣetra, o el campo de actividad del

alma condicionada. Ahora, la persona que se identifica a sí misma con el cuerpo

es llamada kṣetrajña, el conocedor del campo. Es muy difícil entender la

diferencia entre el campo y su conocedor, el cuerpo y el conocedor del cuerpo.

Cualquier

persona puede considerar que desde la infancia hasta la vejez sufre tantos

cambios de cuerpo y sin embargo sigue siendo una persona, permanece. Por lo

tanto hay una diferencia entre el conocedor del campo de actividades y el

verdadero campo de actividades. Un alma

condicionada viviente puede por ello entender que es distinta al cuerpo. Está

descrito en el principio—que la entidad viviente está dentro del cuerpo y que

el cuerpo cambia desde la infancia o niñez y desde la niñez a la juventud y

desde la juventud a la vejez, y la persona que posee el cuerpo sabe que el

cuerpo está cambiando.

El

dueño se distingue ksetrajna. En ocasiones entendemos, estoy contento, estoy

loco, soy una mujer, soy un perro, soy un gato: estos son los conocedores. Los

conocedores se distinguen del campo. Aunque utilicemos muchos artículos- nuestra

ropa, etc- sabemos que somos diferentes a las cosas que usamos. De manera

similar, entendemos con un poco de contemplación que somos diferentes al

cuerpo.”

En los

primeros seis capítulos del Bhagavad-Gīta. El conocedor del cuerpo, la entidad

viviente, y la posición a través de la cual se puede entender al Señor Supremo

son descritas. En medio del sexto capítulo del Gīta, la Personalidad Suprema de

Dios y la relación entre las almas individuales y la Súper-alma con respecto al

servicio devocional son descritas.

La

posición superior de la Personalidad Suprema de Dios y la posición subordinada

del alma individual son definitivamente definidas en estos capítulos. Las

entidades vivientes están subordinadas bajo cualquier circunstancia, pero en su

olvido sufren. Cuando iluminadas por las actividades piadosas, se aproximan al

Señor Supremo con distintas capacidades, como los afligidos, los que desean

dinero, los inquisitivos, o los que buscan conocimiento. Eso también se

describe.

Ahora

empezando con el Capítulo 13º, cómo la entidad viviente llega a estar en

contacto con la naturaleza material, cómo es liberada por el Señor Supremo a

través de distintos métodos o actividades fruitivas, cultivo del conocimiento,

y el desempeño del servicio devocional, se explican. Aunque la entidad es

totalmente distinta al cuerpo, de algún modo se relacionan.”