नारायणं नमस्कृत्य नरं चैव नरोत्तमम्

देवीं सरस्वतीं चैव ततो जयम् उदीरयेत्

महाभरत

महाभरत

Mahābharata

As retold by

Michael Dolan, B.V. Mahāyogi

Nala and Damayanti

|

| Nala leaves Damayanti |

And so Damayanti turned north towards the crystal river, flowing downward to the sea until she reached the holy mountain. The lofty peaks rose up to the heavens. That holy mountain was streaked with veins of precious metals like gold and silver. Through its crags ran clear rivulets filled with opals and other and sacred gemstones. And though those those hills the elephants moved, regal in their bearing.

And as she walked the songs of strange birds consoled her with exotic melodies. There were no palm trees here, but the evergreens of stately height rose over the forest floor. Orange butterflies flitted through blossoming hibiscus as she strode through orchards of trees laden with golden fruits.

Damayanti was lost. Sustained by the golden fruits, she continued on the path. But was this the path to Vidarbha? Or Ayodhya? Or was she only wandering aimlessly, deeper and deeper into the woods?

She felt she was walking in circles, lost and forgotten. Where was Nala? Where was her proud king? Besides herself with the madness of grief, she consulted the trees of the forest, saying, “O majestic lords of the forest, set me free from this misery. Show me the path to my king. Where is Nala?”

And as she passed the trees with golden fruit, she walked another three days further toward the region of the north and by and by she came to a grove of ashoka trees. Within those woods saintly sages had made their ashram.

There, great teachers like Brhigu and Atri and Vasistha had lived from time to time, performing their vows of penance and austerity. Among those sages were mystic yogis who lived on nothing more than air and water, clad in the bark of trees, seeking the right way of living and the path to immortality. Some wore deerskins and sat in the lotus position on mats of kusha straw, meditating on the divine nature. And near them cows were herded, munching grass. Monkeys played in the ashoka trees. Multi-colored parrots sang prayers in sanskrit rhyme. And there the saintly souls had their dwellings made of wood. Plumes of smoke rose from their hearth-fires, warming the cool air.

And while she had wandered long, Damayanti’s courage was revived. Her fair brow shined. A smile graced her cherry-red lips. Her long black tresses moved in the breeze. Her torn sari barely concealed her fine hips and lovely breasts as she strolled into the circle of the holy saints gathered there. And Damayanti wondered to see such holy company sheltered by the green foliage of the ashoka trees. Upon seeing that noble princess enter their grove, the wise men there said arose from their meditation and greeted her.

“Welcome, my child,” said one. “You are home now, my child,” said another.

So cheered by the company of those great souls, that pearl among women, Damayanti took refuge in the mountain ashram. She was offered a seat and some food from the holy offering, prasadam. “Please sit,” they said. “Tell us, how did you find us? How did you arrive here? Where did you come from and what is your purpose?”

“O holy ones, you are all truly blessed, to live here among saintly souls, pursuing the life of dedication to the divine. You are blessed with your sacred fires, your holy worship. O sinless ones, your selfless service is blessed even by the beasts and birds. I think that God in his infinite mercy blesses you in your duties as in your deeds.”

“It is all His grace,” they replied as one. “If we have any goodness here it is by the mercy of our guru, our guide. Our divine mentor has blessed us. But now you have come to bless us with your presence.”

“What goddess are you,” asked one. “Are you the goddess of this forest or of the river? You dazzle us with your beauty. You must be some divine being. Or are you the lady of the mountain, come to bless us in human form?”

“No goddess,” said she. “Neither a river nymph or apsara. I am merely a woman. I am Damayanti, wife of Nala the great hero and king of Nishadha. I am the daughter of King Bhima of Vidarbha, but I have lost my way in this forest. If I cannot find my king I shall surely die of grief.” And she told the sages there of her love for Nala and how the gods had been unkind and he had lost his kingdom by gambling. He is a great king, brave in battle, expert with horses, fierce in war, patient in peace. He is a good ruler to the poor, chastise of the wicked, friendly to brahmanas. Splendid as the king of the gods. Indeed he competed for my hand with Indra himself. Nala is a kind and devoted husband and father. Somehow we were separated. And I have wandered far and long to find him. But I have lost him here in this forest. And now I fear I will lose myself. Has anyone here seen my Nala? Has the monarch of the Nishadhas passed this way? If I don’t find him soon, perhaps I shall leave this mortal body and find the heavenly bliss that you all seek. How can I endure my existence alone, cursed and exiled?”

The sages said: “O blessed one. The time shall come. We see him. By mystic power we can see the future. We see that your future will bring happiness. We see Nala, the tiger of men. You are by his side. But you must first pass through a long time of hardship. You shall be together again. Soon you will behold your king. Mark our words.”

And so saying the saints with their holy fires disappeared from before her eyes. All at once the sacred fires were gone. The holy hermits had vanished. Their humble huts and meditation cells vanished. No smoke came from he sacred fires. They had left no ashes. Even the cows and happy monkeys swinging in the trees had gone, vanished.

The forest floor in the ashoka grove was deserted and dusty.

Damayanti was left standing alone again in the forest. Desolate, she asked the ashoka trees, “Where are all the saints? Where have the hermits gone? Why have they deserted me? Where is my king? Have you seen my husband?”

Mad with grief, she ran from tree to tree, saying, “Where have the holy devotees of Krishna gone? Why have they left me here? Where is the river stream that ran here watering the lotuses? Where are the colorful parrots who chant the holy Vedas in Sanskrit verse?”

She wandered about until she came upon an ashoka tree. Tears in her lotus eyes, she cried, “O noble tree, your name is ashoka, meaning free from lamentation. Free me from my lamentation and tell me where my husband is. He wore the torn half of my cloth. Answer me.”

But the green and leafy tree had no answer.

In this way Damayanti passed through the forest traveling ever deeper into regions dark and dangerous. She passed groves of trees and meandering streams. She passed placid mountains and saw wild deer and birds. She roved over hills and through caverns until she thought she had lost all hope. Arriving at last at a pleasant river, she bathed in its cool, clear waters.

And as she bathed, she saw a cloud of dust across the waters, downstream. It was a large caravan. As the caravan arrived, she could see horses and elephants, chariots and carts laden with goods. They had stopped on the opposite banks of the river and began to ford the waters.

She ran toward them, but the group was astonished to see a disheveled madwoman of the forest running at them and shouting. They stopped.

“Who are you?” They said. “Are you a forest spirit or a demon sent to curse us to hell. Please bless our caravan that we may pass this river with no harm.”

Nala and Damayanti

The Magic Dwarf:

A Race to the Finish

A Race to the Finish

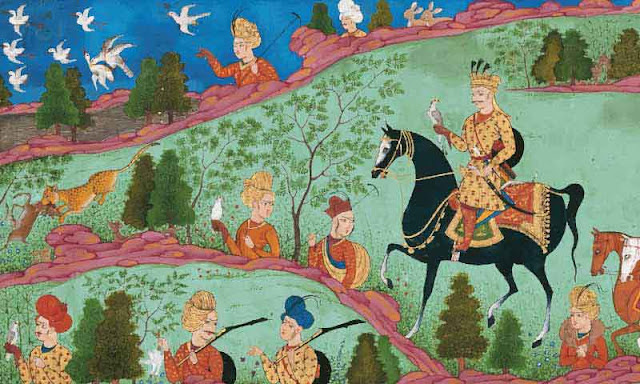

In the kingdom of Ayodhya, Rituparna had made Vahuka the Magic Dwarf, who was really Nala in disguise, his horsemaster. Vahuka was to train Jivala the chariot-driver and see to it that the horses were fast.

Vahuka slept in the stables with the horses. Jivala came to him in the morning, Vahuka led him to the powerful black stallion named Blaze, who had rebelled and thrown the chariot of the king.

“Come here, Jivala,” He said. Blaze’s eyes grew wide as if in terror. “It’s all right boy.” Jivala was afraid of the horse, but followed the instruction. The dwarf was so short he couldn’t reach the horse's neck. He stood up on a wooden stool and held the reins. “Here, boy, don’t be afraid.” Jivala approached.

“Look here,” he said, holding the reins as he stood up on a stool.

Jivala followed, but didn’t understand. What was he supposed to see? He saw a dwarf holding the reins of that hideous beast who had almost killed his master the king.

“What is it, Vahuka?” he said.

“See where the reins chafe the horse’s neck? The straps are too tight.”

“A tight strap makes a good horse,” said Jivala.

“No. This horse is in pain. Remove these reins.”

“Then how shall we control the horse?” said Jivala, who had never heard such nonsense.

“We will control him with love,” said Vahuka. “Do it now.”

He patted the horses face, looking him in the eye, and got down from the stool. Picking up the wooden footstool, he walked across the stable to the next horse.

“Do it now,” he said.

Jivala shook his head. What could a dwarf now about horses? He wasn’t even tall enough to touch his mane.

“Fine. As you say.”

Jivala set about removing the reins. The horse huffed and shook his head. Jivala manhandled the straps. The horse whinnied. Suddenly the dwarf was at his side again, tugging his leg.

“Gently!”

Jivala shrugged. He did his best to undo the straps. He could see that they had chafed through the horse’s skin. As he eased the straps off, a trickle of blood ran down Blaze’s face. He undid the leather straps and stepped back.

“You see, Jivala, this horse is in pain,” said Vahuka. A horse will never respond as long as he is in pain. You must treat him with love, not the whip. No more whip.”

“With all respect, my dear dwarf, I’m not sure I understand your methods. How will the horse go fast if we don’t whip them?”

“They will ride fast as the wind, with only a whisper from you, if you show them love.”

“As you say. You are the horse-master.”

Vahuka handed his assistant a small green bottle with some kind of liquid.

“This is a potion made of herbs. Apply this to his injuries before the blood dries. Do the same for the other horses. I want you to rest all the horses for 3 days.”

Vahuka pointed to the dried and fetid straw piled in the center of the stable.

“Is that their feed?”

“Why yes, sir. The hay comes from town.”

“I want fresh alfalfa.”

“Fresh alfalfa is expensive sir, we’ve always used this hay.”

“This dried hay is not for these champions. They want fresh alfalfa.”

Pointing to the water trough, he said, “How often do you change this water?”

“Why, once a week, sir.”

“No. Change that water now. It’s stagnant. Tell the king you need a helper if must be, but these conditions are not fit for fine horses. If he wants fast horses, they must be happy horses.”

Jivala was beginning to see the logic. He looked down at the strange man with the coal black beard and the winkle in his eye.

“All right sir. I’ll get some helpers.”

A week passed. The stables were clean. The alfalfa was fresh. The mares and foals ate peacefully. The stallions drank pure water. The wild black stallion, Blaze, ran free in the fields of the king without harnesses, straps or reins. All the horses in the stable grew strong. They no longer feared and hated Jivala.

As Jivala worked with a helper to change the water, he felt a tug on his leggings. He turned and saw the coal black eyes of Vahuka looking up at him. “They’re ready. It’s time for a little demonstration,” he said, rubbing his hands together. “Let’s have a race.”

After consultation with the king, a day was set for the race. King Rituparna would select his two best horses. He would race against his famous chariot-driver, Jivala. If Jivala won, he would keep the horse. If the King won, he would give ten cows in charity to the local brahmanas.

The people of Ayodhya turned out to see the spectacle. The weather was fine. They chose a large meadow between the forest of Ayodhya and the fields where the cows grazed. At noon, the spectators sat under brightly colored umbrellas and drank refreshing drinks as the summer sun grew warmer.

First King Rituparna rode forth on a fine white mare, which he called Storm. He was dressed in fine silk cloths and his horse was decorated in Ayodhya’s greatest finery. The horses golden reins and tackle shined in the sun. Jivala was mounted on the fast grey stallion, Thunder. He was wearing the uniform of the king’s charioteers and his horse was decked with silver, the reins fastened tight.

King Rituparna smiled and waved at the crowds gathered there. The townspeople and men of the court cheered their champion. He brought his horse to the line.

Jivala held the reins closely on Thunder. He trotted to the line. A few ladies cheered him from a distance.

Just as the race was about to begin, the crowd broke into laughter. King Rituparna turned to see what the scandal was all about. He could see his hunchbacked horsemaster mounted on Blaze, trotting to the line.

It was a ridiculous sight. The hump-backed dwarf, with his hooked nose, coal black beard and strange garb was riding bare-back, his raven hair wild in the wind. He stood up on the horse’s back, waving at the crowd, and flipped in the air. The crowd went wild at the dwarf’s equestrian antics. As a clown, he was a great success. But in a race with royalty? Blaze didn’t even have a saddle. How could he hope to compete with the king?

He reached the line. King Rituparna looked at the pitiful dwarf mounted on the wildest horse in the stable. “Where’s your saddle?” He said. “I never heard of a race without a saddle.”

“Long ago, in the land of the mlecchas, I learned to ride without a saddle. In the sands of the deserts where the camels roam, the nomads ride bare-back. As your horse-master I should be considered as a candidate for this race.”

The King smiled, “What shall be the stakes?”

“Friendly stakes,” said Vahuka. “I’m tired of the soup you serve around here. I have a mind to show my skill at cooking. If I win, you make me head of your kitchen.”

The horses stamped their feet. Jivala held the reins even tighter. The king laughed. “A horse-master chef? I hope your soup doesn’t smell of the stables.”

The minister of war held a silk handkerchief high in the air. When it fell to the ground the race would begin.

“Very well, Vahuka,” he said. “Take care with that horse. He has a deadly character.

The war minister raised the handkerchief still higher. They readied the horses for a charge. Blaze, Thunder, and Storm tensed the large muscles in their necks. Their eyes bulged.

The silk handkerchief was in the air. The reins tightened. King Rituparna’s horse Storm shot off down the field, his hooves shaking the earth. Dust flew. Jivala was next on Thunder. Blaze trotted down the field. Vahuka smiled peacefully, standing on the horses back and waving to the crowd. The stallion stopped and reached down to taste a flower, unconcerned as the two royal horses sped down the racecourse.

Rituparna had put quite a distance between his own Storm and Jivala’s Thunder.

As they turned the first corner, Vahuka sat down and stroked the horse’s mane, fondly. “Run like the wind," he whispered in the horse’s ear.”

Suddenly Blaze bolted into action. His head went horizontal, his teeth were gritted, his eyes showed white. He seemed to fly above the earth. He charged, his hooves thundering over the turf, as he carried the dwarf Vahuka just as the wind carries a leaf.

Jivala felt a rush of air as Blaze raced past, nostrils flared. The dwarf smiled at him as he pulled even tighter on the reins. He wanted to reach for the whip, but the whip had been banned.

But Vahuka needed no whip. He whispered again to Blaze as they rocketed past Jivala on Thunder.

King Rituparna was still far ahead, nearing the finish line. Some of the crowd cheered the king, but others began cheering the dwarf who was closing. Jivala was far behind as Blaze kicked up the dust.

As they came into the final turn, Rituparna smiled. It would be an easy victory. The brahmanas would be happy with their new cows. He could hear the crowd cheering him on.

As they came into the stretch, Vahuka on Blaze was inching up on Storm. Both horses were straining to run as fast as they could, but Blaze was running without the weight of a saddle, without the chafing of the bridle, and his rider ran without the restraints of a king’s rich garments. Leaning forward, the dwarf whispered again. Blaze ran even faster.

Rituparna was shocked. “Who is this dwarf?” He thought, “Is he a Gandharva in disguise?” just as Vahuka raced past. He pushed Storm to respond, but the horse could run no faster.

In a trifle, the race was over. Vahuka rode Blaze fast as the wind to the finish line. King Rituparana arrived a full second later. They waited a bit for Jivala, whose horse Thunder was exhausted. The crowd cheered the victor. “Hurray for Vahula! Hurray for the Dwarf! Vahula ki Jai!” they shouted.

After the race, King Rituparna congratulated Vahuka and appointed him master of the kitchens. The following day, Vahuka prepared a great feast for all. Brahmanas were invited to the feast which was served at an auspicious hour. After an aroti ceremony offering everything to the Deity of Vishnu, all were served. They sat in the courtyard in the shade of a huge tamarind tree. There were rich subjis, simple rice dishes with saffron soaked in ghee or clarified butter. There were refreshing drinks and payasam, sweet rice. A large variety of fresh fruits, vegetables, and different kinds of savories, samosas, and pakoras were served, followed by a number of desserts. Everyone agreed that Vahuka was quite a cook.

Two of the brahmanas there had traveled from the court of King Bhima in Vidarbha. As they were eating, one of them said, “I have traveled far and wide in the kingdom of Ayodhya and have never seen anyone with such skill at horses.”

His friend said, “There is only one man capable of such a feat. But alas, he was exiled to the forest by the cruel King Pushkar after losing everything in a dice game.”

The first brahmana laughed: “You must mean King Nala. Nala was tall with curly golden hair. This Vahuka is a clown. He may be good with horses but he has nothing in common with King Nala.”

His friend smiled as he licked a bit of buttery rice from his finger, “He has another thing in common with Nala. This saffron rice. I have only tasted rice like this once before; in the kingdom of Vishadha at the feast of Damayanti.”

“You're right my friend. It may be that Nala has come upon hard times and disguised himself. We must return to Vidarbha and inform the King of these strange events.”

And after finishing their meal the two brahmanas excused themselves and set off on the road to Vidarbha and King Bhima.

महाभरत

महाभरत

Mahābharata

As retold by

Michael Dolan, B.V. Mahāyogi

Nala and Damayanti

The Stampede of the Wild Elephants

When she saw the caravan fording the river, downstream, Damayanti rubbed her eyes. Was this a dream? Would they disappear like the holy hermits in the enchanted forest?

They began to wade across. There were men dressed in the style of merchants, horses, asses laden with goods and bullock carts whose heavy wheels wore grooves in the mud. The men helped guide the carts across the river.

The water was only knee-deep at the ford. The reeds grew tall, and geese played on the waveless water. A few women carrying baskets began across, as the men with the carts reached the cane bushes on the near side.

Damayanti realized then that this was not a dream. For the first time in days she was close to civilization. These people would help her recover her Nala. She ran to them, waving her arms in desperation.

The men and women of the caravan saw a madwoman running toward them waving her arms. They shrank from the slender-waisted Damayanti. Half-clad in a torn sari she seemed like a maniac, thin and pallid. Her locks were all matted and covered with dust. Some ran in terror from this river spirit. Others approached her in pity and asked, “Who are you? Are you a spirit of this wood? Are you a yaksha or a rakshasa who protects these waters? If you are some divine god, bless us poor merchants who are on our way to market in the city of Chedi which lies through through these woods some leagues away.”

And Damayanti said, “I am only a poor girl who has lost her way. I am the daughter of Bhima, king of Vidarbha. I am looking for my great husband, the king Nala, ruler of the Nishadhas, who has lost his kingdom and been exiled to the forest. Please tell me if you have seen him pass by here.”

Now, the leader of that caravan was a merchant man named Suchi. He said, “O queen, daughter of Vidarbha, we have seen no such man or king pass this way. We have marched for many a day through this forest and have seen neither man nor woman. Elephants and leopards haunt these perilous woods. We have seen buffaloes, tigers, and bears. But no men.”

“Good sir, tell me where you and your company are bound,” she said.

“We are heading for the city of Lord Suvaha, the honest and truth-telling king of the Chedis. Join us, for we shall take you back to civilization through this dark and terrible forest. This is no place for a young and beautiful girl such as you.”

They made camp for the night on the banks of that placid stream. Damayanti bathed, and was given fresh cloth by some of the women of the merchants. And after eating a hot meal in the company of the ladies there, she rested. On the following day, Damayanti joined the caravan’s march as they went through the forest on the way to Chedi.

After a three day march, they left the dark and awful forest and arrived at the shores of a great lake, covered with lotuses. All around the lake were unusual flowers, bamboo and sugar cane.

The water of the lake was crystal pure and refreshing. There was plenty of grass for the horses and oxen, and plenty of sweet sugar cane. It was a natural oasis of fruits and flowers, coconuts and bananas, lotuses and kadamba flowers. Melodious birds filled the air with song.

Their leader, Suchi, signalled to make camp there. And they found delightful shelter in that pleasant grove.

But that land was the favorite of the elephants. And as they slept, a group of wild elephants came from out the forest and began to run to the lotus-filled lake to drink and bathe themselves and to feast on the sugar cane.

Those mighty beasts ran right through the pleasant groves where the caravan lay sleeping. And as the merchants arose and tried to defend themselves, waving their arms and screaming, there the elephants panicked.

The elephant herd charged and stampeded, crushing horses and camels; and in their wild rampage they killed some of the merchants with their tusks and others by trampling.

Some of the merchants ran in terror only to be trampled. Others climbed trees to escape the charging elephants who did great destruction to the caravan and to their camp.

Some uttered cries of terror as they were crushed beneath the powerful legs of the mad elephants.

In the chaos, some men drew swords and spears. They threw their spears at the elephants, killing other men.

And so it was that the caravan that had rescured Damayanti suffered great loss on account of the elephants. The campfires were overturned. The flames became a raging fire burning through the sugar cane. And the conflagration reached even the men who had hidden in the trees. And there arose a tremendous uproar like to the destruction of the three worlds at the end of time.

In the morning the elephants had gone. And some of the more unscrupulous followers of the caravan had gathered the jewels and gold of the others and made off with their wealth, fleeing the camp. Others merely fled the frantic carnage, returning to the river from whence they came.

And as the sun came up, those who were left behind wondered much at these occurrences saying, “Such misfortune has never befallen us before. Perhaps we have offended some spirit of the forest.”

Envious tongues blamed Damayanti, saying, “Yes. We were fine before that madwoman arrived. She must be a Rakshasa, or some other supernatural being or a demon sent from hell to torture us.”

When she awoke, she could hear the others talking. Damayanti took shelter behind a tree and listened as the others conspired against her.

“This demon-girl is bad luck. We should kill her,” said one.

“She must be a Rakshasa who bewildered our leaders with her beauty. But she must be stopped before her magic kills us all..”

One of the elders who had survived said, “She should be stoned to death. Or left to be trampled by the elephants.”

Another said, “She must be drowned in her own lake. Or beaten to death with our very fists, the she-devil.”

An old woman said, “Who is this woman? She brought evil upon us. Did you see her maniac eyes, her barely-human form? She is a witch whose black magic has cursed us all to death. Who else but a demon would cause us harm. Let us set upon her with stones and bamboo sticks. We must put her to death or perish ourselves.”

In terror and shame Damayanti fled to the shade of the forest. There she found a path that wound around the other side of the lake where there were no flowers but only brambles and thorns. Her bare feet bled to step on the rocky path.

“Why am I so cursed? Could the gods be so angry with me? What was my sin? I scarcely met this host of men when they were slaughtered by mad elephants. But my accursed life was spared, that I might spend more time in sorrow. No one dies before his time, they say. And what befalls us, good our bad is our own destiny. And yet, even as a child I never did anything so sinful as to cause such a terrible reaction. I must have offended the gods at my swayamvara. I rejected them for Nala. Perhaps had I chosen a god for my husband, I wouldn’t find myself lost in this terrible forest. But how could I have chosen otherwise. Nala was my destiny.”

And so, lamenting her fate, Damayanti walked on towards the sunset. And as she came over a small rise in the footpath, she could see, shining in the distance the stone towers of the city of Suvahu the truth-seeking king of the Chedis. At last.

नारायणं नमस्कृत्य नरं चैव नरोत्तमम्

देवीं सरस्वतीं चैव ततो जयम् उदीरयेत्

महाभरत

महाभरत

Mahābharata

As retold by

Michael Dolan, B.V. Mahāyogi

Nala and Damayanti

The Magic Dwarf:

"Where has she gone?"

"Where has she gone?"

Brihadaswa said, “Late at night, Jivala was passing by the stables. He could see the light of a candle flickering through a window. He approached and heard the plaintiff sound of a lute, accompanied by a low, gruff voice. The dwarf was singing.

Curious, Jivala came closer to the window. He could see the dwarf playing a curious musical instrument. As he listened, he could hear Vahuka sing a sad and original ballad about a king who loses his empire. “What a strange song,” thought the king. He walked to the door of the stables and entered quietly, but As he approached, the dwarf stopped singing and put down his lute.

“Vahuka,” said the Jivala. “Don’t stop. I just came to sweep up the stables. I must confess, you have surprised us all. I never thought you would outrace the king of Ayodhya. And all the royal guests at court are satisfied. The brahmanas there have never tasted such rich food. Your feast was quite a success. And they’re all talking about the horse race. I must say, you’ve made quite a reputation here in Ayodhya, my dear little dwarf. And now it turns out you play the lute. I’m sorry to interrupt, you sir. Please continue your song.”

And Vahuka the dwarf looked at his friend Jivala. He picked up his lute again. He said, “Very well, my lord. I’m not much of a singer. But my song tells an old story. Perhaps you’ve heard it before. And he sang Jivala a strange ballad of a far off kingdom where a great and noble king ruled. He was married to a fair princess, who had chosen him from among the gods.

He ruled peacefully for twelve years, but one day, the king broke ekadashi. and fell under the influence of a demon, Kali. Possessed by the demon he played at dice and lost his kingdom. Exiled to the forest, he abandoned his wife, was bitten by a snake-prince, and became an ugly dwarf, bound to train horses.

When he finished Jivala was astonished. “What could it mean?” he though. “Was Vahuka telling his life in song? Was he accursed or possessed by some strange demon?”

“That’s a strange song,” he said. “And so sad. Is this your composition?”

Vahuka smiled. “Like most sad ballads, this one tells an unbelievable story, and yet it reminds me of someone and the melody is not without merit.”

“But you have traveled far and wide,” said Jivala, suspecting that Vahuka wasn’t telling the whole story. “Have you ever known anyone like this king who wagered his empire at dice?”

“Such things only happen in ballads, my friend” said the mysterious dwarf. He smiled widely, showing his broken teeth between his coal black beard as he slipped the ivory plectrum between the strings and put up his lute. “I’m glad the people enjoyed the feast. What does his lordship like for breakfast?”

“It’s such a sad ballad. There must be some truth in it,” said Jivala who stood in the stable doorway, leaning on his broom.

“Well, according to the poets, the sweetest songs sing of the saddest things.”

“Yes, but the song seems personal to you. What about the dwarf?”

“Oh, the old ballads are filled with dwarfs and dragons, Nagas, yakshas and rakshasas. You mustn’t take these things seriously. Surely they have been made up by poets to scare children into going to bed early. There are many such songs.”

“Do you know any others?” said Jivala.

“Oh, all right. If you like,” said the dwarf. He picked up his lute and took the plectrum from the strings. And once again he began to play and sing:

क्व नु सा क्षुत्पिपासार्ता श्रान्ता शेते तपस्विनी ।

स्मरन्ती तस्य मन्दस्य कं वा साद्योपतिष्ठति ॥

kva nu sā kṣutpipāsārtā śrāntā śete tapasvinī |

smarantī tasya mandasya kaṃ vā sādyopatiṣṭhati ||

smarantī tasya mandasya kaṃ vā sādyopatiṣṭhati ||

“Where is she, worn and weary? Where is she, hungry and thirsty and torn by penance. Where does she rest?

Does she remember the fool who left her? And who is she serving now? O where has she gone?”

Does she remember the fool who left her? And who is she serving now? O where has she gone?”

And Jivala said, “Who might be the lady’s husband?”

“The song tells of a man who lost his sense. The lady is faultless. But this fool leaves her, possessed by ghosts. And so he wanders, racked by sorrow.

"The wretch made false promises. He cannot rest by day or night. And so at night, he remembers her, singing this song, ‘O where has she gone?’ You want to hear the rest?”

"The wretch made false promises. He cannot rest by day or night. And so at night, he remembers her, singing this song, ‘O where has she gone?’ You want to hear the rest?”

“Play on,” said Jivala.

And taking up his theme again, Vahuka sang,

“Having wandered the whole round world, the wretch can’t sleep at night.

His soul possessed by Kali, his mind consumed with fright.

He broods and sings this verse of grief, it gives him some relief.

‘O where O where has my lady gone; he left her like a thief

Abandoned in the forest dark, the forest lone and dread.

O where O where has my lady gone? Alive? Or is she dead?

Dead to the love that we once had, lost to beasts of prey?

O where has she gone, where does she roam?

Her lord has gone away.’”

From Mahābhārata 3.64.9–19

11 evaṃ bruvantaṃ rājānaṃ niśāyāṃ jīvalo 'bravīt

kām enāṃ śocase nityaṃ śrotum icchāmi bāhuka

12 tam uvāca nalo rājā mandaprajñasya kasya cit

āsīd bahumatā nārī tasyā dṛḍhataraṃ ca saḥ

13 sa vai kena cid arthena tayā mando vyayujyata

viprayuktaś ca mandātmā bhramaty asukhapīḍitaḥ

14 dahyamānaḥ sa śokena divārātram atandritaḥ

niśākāle smaraṃs tasyāḥ ślokam ekaṃ sma gāyati

15 sa vai bhraman mahīṃ sarvāṃ kva cid āsādya kiṃ cana

vasaty anarhas tadduḥkhaṃ bhūya evānusaṃsmaran

16 sā tu taṃ puruṣaṃ nārī kṛcchre 'py anugatā vane

tyaktā tenālpapuṇyena duṣkaraṃ yadi jīvati

17 ekā bālānabhijñā ca mārgāṇām atathocitā

kṣutpipāsāparītā ca duṣkaraṃ yadi jīvati

18 śvāpadācarite nityaṃ vane mahati dāruṇe

tyaktā tenālpapuṇyena mandaprajñena māriṣa

19 ity evaṃ naiṣadho rājā damayantīm anusmaran

ajñātavāsam avasad rājñas tasya niveśane

|

11 एवं बरुवन्तं राजानं निशायां जीवलॊ ऽबरवीत

काम एनां शॊचसे नित्यं शरॊतुम इच्छामि बाहुक

12 तम उवाच नलॊ राजा मन्दप्रज्ञस्य कस्य चित

आसीद बहुमता नारी तस्या दृढतरं च सः

13 स वै केन चिद अर्थेन तया मन्दॊ वययुज्यत

विप्रयुक्तश च मन्दात्मा भरमत्य असुखपीडितः

14 दह्यमानः स शॊकेन दिवारात्रम अतन्द्रितः

निशाकाले समरंस तस्याः शलॊकम एकं सम गायति

15 स वै भरमन महीं सर्वां कव चिद आसाद्य किं चन

वसत्य अनर्हस तद्दुःखं भूय एवानुसंस्मरन

16 सा तु तं पुरुषं नारी कृच्छ्रे ऽपय अनुगता वने

तयक्ता तेनाल्पपुण्येन दुष्करं यदि जीवति

17 एका बालानभिज्ञा च मार्गाणाम अतथॊचिता

कषुत्पिपासापरीता च दुष्करं यदि जीवति

18 शवापदाचरिते नित्यं वने महति दारुणे

तयक्ता तेनाल्पपुण्येन मन्दप्रज्ञेन मारिष

19 इत्य एवं नैषधॊ राजा दमयन्तीम अनुस्मरन

अज्ञातवासम अवसद राज्ञस तस्य निवेशने

|