Snake Prince, Thailand

Michael Dolan, B.V. Mahāyogi

The Search for Damayanti Begins

Meanwhile, in the Kingdom of Vidarbha, King Bhima was worried. His daughter’s children had arrived by chariot a fortnight since. The king was well-pleased to see them.

“Grandfather!” they said, running from the chariot and throwing their arms around him.

“Let me look at you, children,” he said, a warm smile masking his concern.

They had grown. Had it really been 12 years since the swayamvara and the wedding? Indrasen already had his father’s curly hair, piercing eyes and proud gait, and Indrasena while only a girl had her mother’s grace and quiet beauty.

The children blushed and laughed. As Varshneya the charioteer tied up the horses, Indrasen and Indrasena frolicked away to play in the gardens where once a swan messenger had brought news of a handsome prince to the virgin Damayanti.

|

| King Bhima, Artist's conception |

Brim approached the chariot-driver as he watered the horses. “O Varshneya, best of horsemen, accept my blessings. Gold and silver will be yours for having brought my grand-children safely from the land of Vishadha. But what’s the news, my friend. Where is my daughter? Is she arriving here soon with King Nala to visit?” said Bhima.

|

| Ancient Gold Coins of Vidarbha, India, 800 B.C |

Varshneya looked at his hands. “I have brought the children here on my lady Damayanti’s orders. She foresaw the tragedy and sent me here.”

“What tragedy, sir?” said the King.

“All is lost. The king’s brother used some mystic charm to cheat the king. I felt some evil influence enter the gaming hall. King Nala staked everything and lost.

|

| The dice game of Nala and Pushkar: Rival brothers |

They gamed at dice for days until Nala lost everything. He was banished into the forest, stripped of all his wealth and left to die of starvation, abandoned by the citizens by order of his cruel brother. The king is under some spell. He wanders lost in the dark forest. At last, our lady Damayanti followed him into the woods.”

King Bhima of Vidarbha heard the news of the exile with dismay. What on earth had happened his son-in-law, King Nala? What could have possessed him to lose his kingdom in a dice game? How could Nala’s brother Pushkar have been capable of such treachery?

Varshneya told of Pushkar’s treachery. How he had ordered his citizens to shun Nala. Anyone who helped him did so on pain of death. None could offer him food or shelter. Cruel and envious, Pushkar had prevailed upon the miserable Nala to wager his own wife in the game. But Nala had refused. Having lost the game, he went to the woods as an honorable man according to the terms of the wager. But Pushkar had surely cheated him at dice. Perhaps Nala had been poisoned or enchanted in some way.

|

| Woods near Vidarbha, present day |

In the course of the day, King Bhima situated his grandchildren in fine apartments within the palace. His royal servants did everything to take care of them and make them comfortable. Soon they would miss there mother. But where was Damayanti?

As night fell, King Bhima sent for the brahmanas who frequented his court. He personally washed their feet, offered them all respect, and fed them well. And when they were satisfied they asked, “my dear King, why have you sent for us?”

The king said, “Alas. No one knows the fate of Nala, my erstwhile son-in-law. He was exiled into the forest by his cruel brother who cheated him at dice. Having gambled everything away, he was scorned, driven from his kingdom, banished and left to die alone in the forest. My daughter, the fair Damayanti, Princess of Vidarbha, has followed him into exile. Woe is me. What shall I do? I need some good counsel in this matter.”

Now the foremost of those good souls stepped forward and said, “Let us go forth and search for your daughter and for Nala, King of Vishadha. If they are alive, we shall find them.

And King Bhima said, “So be it. Go forth throughout the land. Announce far and wide that King Bhima is desirous to see his daughter Damayanti. Whosoever brings news to me of my daughter shall be well-rewarded for his pains.

“Discover the whereabouts of King Nala. Who brings Nala or Damayanti home shall receive from me cows and land. Anyone who brings news of my children shall receive gold and silver. You pious and compassionate brahmanas can help me, for by your mercy I shall recover the jewel of my kingdom, my fair daughter, Damayanti.”

And so it was that the brahmanas left, early in the morning in search of King Bhima’s daughter. They went in all directions, from town to town, but no one had heard any news. Nala and his wife could not be found in any of the towns or provinces near the kingdom of Vidarbha. As time passed, King Bhima himself was disconsolate. Where was Damayanti?

|

| The Vidarbha Express train, Present Day |

Michael Dolan, B.V. Mahāyogi

Nala and Vahuka: The Magic Dwarf

As the strange snake prince disappeared into the forest, Nala was confused. His body burned with the snakebite.

Bt as the poisonous venom coursed through his veins, his head became clear for the first time in days. He looked at himself again in the mirror of the stream and saw the ugly face of a twisted old dwarf with buck-teeth and bushy eyebrows. A coal-black beard completed his hideous appearance. Short and stout, he was dressed as a chariot driver. No, his own chariot-driver, Varshneya was better dressed. What had become of Varshneya, he wondered.

Suddenly, he remembered Damayanti. What had he done? What had possessed him to leave her in the forest? As the influence of Kali diminished, his conscience pricked him. But this was no time for lamentation. The snake venom moved through him, emboldening his steps. What had the Naga prince said? He must go to the city of Ayodhya, where once Lord Rāma had ruled so long ago. There he could bide his time until the moment came for him to regain his kingdom. There was still hope.

He stood up straight and dusted himself off. The acrid smell of burned wood still hung in the air. But now the sun was coming up over the mountains and he could see the path to Ayodhya through the mist.

“My name is Vahuka now,” Nala thought. Glancing again at his mirror image in the stream, he smiled. “Yes, the Naga was right. This is the perfect disguise. Who will recognize me? I will take the path to Ayodhya and seek out the king there. What was his name? Rituparna. I will go to Rituparna and train horses for a while.”

And so it was that Nala, in the form of the dwarf Vahuka, began walking down the forest path to Ayodhya, where after a few days he arrived. Making his way through the great gate of the city he reached the palace of the king whose name was Rituparna. “Vahuka is my name,” he sang, “and horses are my game.”

As luck would have it, Rituparna himself was just entering the palace courtyard, seated on his chariot. But the horses were upset. They pulled the chariot in all directions.

“Hold!” said his chariot-driver, as he pulled on the reins. The horses reared, baring their white teeth. They refused to obey. The chariot overturned.

Rituparna was cast to the ground. Grabbing the reins, the chariot-driver lashed a black stallion with his whip, trying to bring him under control. The horse reared again, attacking the driver. Rituparna was trapped under a broken axle of the overturned chariot. With hatred in his eyes the furious stallion made to trample the king. The chariot driver, whip in hand, ran from the maddened beast.

Just then the king saw an ugly dwarf, robust and muscular, stand before the raging horses. He put his stubby fingers in his mouth and whistled through his beard. The horses looked at him. They shook out their manes. He whispered a mantra in a foreign language. They stamped their hooves and switched their tails and then stood quietly, as if thoughtful. He approached the angry black stallion. Unable to reach any higher, he patted the horse on the shank. “ Stay.” He said. “It’s me. Stay now. That’s good.” The horse stood calmly, happy to receive the affectionate touch of Vahuka the dwarf.

Having calmed the horses, the powerful dwarf bent over the king and lifted the chariot wheel from where it was crushing his chest. He helped Rituparna to his feet. “Who are you?” said the king with a smile, dusting himself off.

“Vahuka is my name, and horses are my game.”

“I can see that,” said the king. “You’re just in time. I’m afraid my chariot driver is not very experienced.”

By this time the driver had returned, chastened by the accident. “Jivala! Get back here.” The king said. “Meet Vahuka. He’s our new horse-trainer. You can learn a lot from this man.” Turning to Vahuka, the king said, “You will help us won’t you?”

Vahuka the magic dwarf bowed low before the king. "Allow me to introduce myself," he said. "I am Vahuka. No one on earth is my equal at taming wild stallions, harnessing fiery steeds to a chariot or racing horses. I give wise counsel in affairs of state and am no stranger to the use of arms. I am expert in the culinary arts and sciences. By simple touch, I produce fire."

And indeed by snapping his fingers, sparks flew. They fell on the dry straw on the earth near the chariot. The straw produced an ember which fanned by a slight breeze burst into a tiny flame.

"I can also call water from anywhere." And snapping his fingers again and touching the earth a trickle of water sprang from the ground and extinguished the fire.

Jivala, who stood there, whip in hand, was astonished. "This dwarf is surely magic!" he said to the king.

Vahuka continued, "I am well-known for my art in cooking. I was on my way to Vidarbha or perhaps Nishadha, for these kingdoms have a good reputation, but as I am fond of Lord Rāma, I couldn't possibly omit a visit to fair Ayodhya, Rāma's kingdom."

And King Rituparna said, "O Magic Dwarf, Vahuka. You have shown your prowess with horses. I am sure you are every bit as expert in the kitchen as you are in the stables. Stay here with us in Ayodhya. Help me with my horses. I shall pay you gold and silver coins of the realm. I shall appoint you stable-master. Jivala here shall assist you in anything you need."

Vahuka again bowed with a flourish. "As you wish, sire." he said.

नारायणं नमस्कृत्य नरं चैव नरोत्तमम्

देवीं सरस्वतीं चैव ततो जयम् उदीरयेत्

Michael Dolan, B.V. Mahāyogi

Nala and Damayanti

|

| Nala leaves Damayanti |

And so Damayanti turned north towards the crystal river, flowing downward to the sea until she reached the holy mountain. The lofty peaks rose up to the heavens. That holy mountain was streaked with veins of precious metals like gold and silver. Through its crags ran clear rivulets filled with opals and other and sacred gemstones. And though those those hills the elephants moved, regal in their bearing.

And as she walked the songs of strange birds consoled her with exotic melodies. There were no palm trees here, but the evergreens of stately height rose over the forest floor. Orange butterflies flitted through blossoming hibiscus as she strode through orchards of trees laden with golden fruits.

Damayanti was lost. Sustained by the golden fruits, she continued on the path. But was this the path to Vidarbha? Or Ayodhya? Or was she only wandering aimlessly, deeper and deeper into the woods?

She felt she was walking in circles, lost and forgotten. Where was Nala? Where was her proud king? Besides herself with the madness of grief, she consulted the trees of the forest, saying, “O majestic lords of the forest, set me free from this misery. Show me the path to my king. Where is Nala?”

And as she passed the trees with golden fruit, she walked another three days further toward the region of the north and by and by she came to a grove of ashoka trees. Within those woods saintly sages had made their ashram.

There, great teachers like Brhigu and Atri and Vasistha had lived from time to time, performing their vows of penance and austerity. Among those sages were mystic yogis who lived on nothing more than air and water, clad in the bark of trees, seeking the right way of living and the path to immortality. Some wore deerskins and sat in the lotus position on mats of kusha straw, meditating on the divine nature. And near them cows were herded, munching grass. Monkeys played in the ashoka trees. Multi-colored parrots sang prayers in sanskrit rhyme. And there the saintly souls had their dwellings made of wood. Plumes of smoke rose from their hearth-fires, warming the cool air.

And while she had wandered long, Damayanti’s courage was revived. Her fair brow shined. A smile graced her cherry-red lips. Her long black tresses moved in the breeze. Her torn sari barely concealed her fine hips and lovely breasts as she strolled into the circle of the holy saints gathered there. And Damayanti wondered to see such holy company sheltered by the green foliage of the ashoka trees. Upon seeing that noble princess enter their grove, the wise men there said arose from their meditation and greeted her.

“Welcome, my child,” said one. “You are home now, my child,” said another.

So cheered by the company of those great souls, that pearl among women, Damayanti took refuge in the mountain ashram. She was offered a seat and some food from the holy offering, prasadam. “Please sit,” they said. “Tell us, how did you find us? How did you arrive here? Where did you come from and what is your purpose?”

“O holy ones, you are all truly blessed, to live here among saintly souls, pursuing the life of dedication to the divine. You are blessed with your sacred fires, your holy worship. O sinless ones, your selfless service is blessed even by the beasts and birds. I think that God in his infinite mercy blesses you in your duties as in your deeds.”

“It is all His grace,” they replied as one. “If we have any goodness here it is by the mercy of our guru, our guide. Our divine mentor has blessed us. But now you have come to bless us with your presence.”

“What goddess are you,” asked one. “Are you the goddess of this forest or of the river? You dazzle us with your beauty. You must be some divine being. Or are you the lady of the mountain, come to bless us in human form?”

“No goddess,” said she. “Neither a river nymph or apsara. I am merely a woman. I am Damayanti, wife of Nala the great hero and king of Nishadha. I am the daughter of King Bhima of Vidarbha, but I have lost my way in this forest. If I cannot find my king I shall surely die of grief.” And she told the sages there of her love for Nala and how the gods had been unkind and he had lost his kingdom by gambling. He is a great king, brave in battle, expert with horses, fierce in war, patient in peace. He is a good ruler to the poor, chastise of the wicked, friendly to brahmanas. Splendid as the king of the gods. Indeed he competed for my hand with Indra himself. Nala is a kind and devoted husband and father. Somehow we were separated. And I have wandered far and long to find him. But I have lost him here in this forest. And now I fear I will lose myself. Has anyone here seen my Nala? Has the monarch of the Nishadhas passed this way? If I don’t find him soon, perhaps I shall leave this mortal body and find the heavenly bliss that you all seek. How can I endure my existence alone, cursed and exiled?”

The sages said: “O blessed one. The time shall come. We see him. By mystic power we can see the future. We see that your future will bring happiness. We see Nala, the tiger of men. You are by his side. But you must first pass through a long time of hardship. You shall be together again. Soon you will behold your king. Mark our words.”

And so saying the saints with their holy fires disappeared from before her eyes. All at once the sacred fires were gone. The holy hermits had vanished. Their humble huts and meditation cells vanished. No smoke came from he sacred fires. They had left no ashes. Even the cows and happy monkeys swinging in the trees had gone, vanished.

The forest floor in the ashoka grove was deserted and dusty.

Damayanti was left standing alone again in the forest. Desolate, she asked the ashoka trees, “Where are all the saints? Where have the hermits gone? Why have they deserted me? Where is my king? Have you seen my husband?”

Mad with grief, she ran from tree to tree, saying, “Where have the holy devotees of Krishna gone? Why have they left me here? Where is the river stream that ran here watering the lotuses? Where are the colorful parrots who chant the holy Vedas in Sanskrit verse?”

She wandered about until she came upon an ashoka tree. Tears in her lotus eyes, she cried, “O noble tree, your name is ashoka, meaning free from lamentation. Free me from my lamentation and tell me where my husband is. He wore the torn half of my cloth. Answer me.”

But the green and leafy tree had no answer.

In this way Damayanti passed through the forest traveling ever deeper into regions dark and dangerous. She passed groves of trees and meandering streams. She passed placid mountains and saw wild deer and birds. She roved over hills and through caverns until she thought she had lost all hope. Arriving at last at a pleasant river, she bathed in its cool, clear waters.

And as she bathed, she saw a cloud of dust across the waters, downstream. It was a large caravan. As the caravan arrived, she could see horses and elephants, chariots and carts laden with goods. They had stopped on the opposite banks of the river and began to ford the waters.

She ran toward them, but the group was astonished to see a disheveled madwoman of the forest running at them and shouting. They stopped.

“Who are you?” They said. “Are you a forest spirit or a demon sent to curse us to hell. Please bless our caravan that we may pass this river with no harm.”

The Magic Dwarf:

A Race to the Finish

In the kingdom of Ayodhya, Rituparna had made Vahuka the Magic Dwarf, who was really Nala in disguise, his horsemaster. Vahuka was to train Jivala the chariot-driver and see to it that the horses were fast.

Vahuka slept in the stables with the horses. Jivala came to him in the morning, Vahuka led him to the powerful black stallion named Blaze, who had rebelled and thrown the chariot of the king.

“Come here, Jivala,” He said. Blaze’s eyes grew wide as if in terror. “It’s all right boy.” Jivala was afraid of the horse, but followed the instruction. The dwarf was so short he couldn’t reach the horse's neck. He stood up on a wooden stool and held the reins. “Here, boy, don’t be afraid.” Jivala approached.

“Look here,” he said, holding the reins as he stood up on a stool.

Jivala followed, but didn’t understand. What was he supposed to see? He saw a dwarf holding the reins of that hideous beast who had almost killed his master the king.

“What is it, Vahuka?” he said.

“See where the reins chafe the horse’s neck? The straps are too tight.”

“A tight strap makes a good horse,” said Jivala.

“No. This horse is in pain. Remove these reins.”

“Then how shall we control the horse?” said Jivala, who had never heard such nonsense.

“We will control him with love,” said Vahuka. “Do it now.”

He patted the horses face, looking him in the eye, and got down from the stool. Picking up the wooden footstool, he walked across the stable to the next horse.

“Do it now,” he said.

Jivala shook his head. What could a dwarf now about horses? He wasn’t even tall enough to touch his mane.

“Fine. As you say.”

Jivala set about removing the reins. The horse huffed and shook his head. Jivala manhandled the straps. The horse whinnied. Suddenly the dwarf was at his side again, tugging his leg.

“Gently!”

Jivala shrugged. He did his best to undo the straps. He could see that they had chafed through the horse’s skin. As he eased the straps off, a trickle of blood ran down Blaze’s face. He undid the leather straps and stepped back.

|

| Ancient Coin with Horse Race |

“You see, Jivala, this horse is in pain,” said Vahuka. A horse will never respond as long as he is in pain. You must treat him with love, not the whip. No more whip.”

“With all respect, my dear dwarf, I’m not sure I understand your methods. How will the horse go fast if we don’t whip them?”

“They will ride fast as the wind, with only a whisper from you, if you show them love.”

“As you say. You are the horse-master.”

Vahuka handed his assistant a small green bottle with some kind of liquid.

“This is a potion made of herbs. Apply this to his injuries before the blood dries. Do the same for the other horses. I want you to rest all the horses for 3 days.”

Vahuka pointed to the dried and fetid straw piled in the center of the stable.

“Is that their feed?”

“Why yes, sir. The hay comes from town.”

“I want fresh alfalfa.”

“Fresh alfalfa is expensive sir, we’ve always used this hay.”

“This dried hay is not for these champions. They want fresh alfalfa.”

Pointing to the water trough, he said, “How often do you change this water?”

“Why, once a week, sir.”

“No. Change that water now. It’s stagnant. Tell the king you need a helper if must be, but these conditions are not fit for fine horses. If he wants fast horses, they must be happy horses.”

Jivala was beginning to see the logic. He looked down at the strange man with the coal black beard and the winkle in his eye.

“All right sir. I’ll get some helpers.”

|

Ancient Horses grazing

|

A week passed. The stables were clean. The alfalfa was fresh. The mares and foals ate peacefully. The stallions drank pure water. The wild black stallion, Blaze, ran free in the fields of the king without harnesses, straps or reins. All the horses in the stable grew strong. They no longer feared and hated Jivala.

As Jivala worked with a helper to change the water, he felt a tug on his leggings. He turned and saw the coal black eyes of Vahuka looking up at him. “They’re ready. It’s time for a little demonstration,” he said, rubbing his hands together. “Let’s have a race.”

|

| Assyrian Winged Horses |

After consultation with the king, a day was set for the race. King Rituparna would select his two best horses. He would race against his famous chariot-driver, Jivala. If Jivala won, he would keep the horse. If the King won, he would give ten cows in charity to the local brahmanas.

|

| Gold Coin showing horse racing issued by Philip of Macedonia circa 500 BC |

The people of Ayodhya turned out to see the spectacle. The weather was fine. They chose a large meadow between the forest of Ayodhya and the fields where the cows grazed. At noon, the spectators sat under brightly colored umbrellas and drank refreshing drinks as the summer sun grew warmer.

|

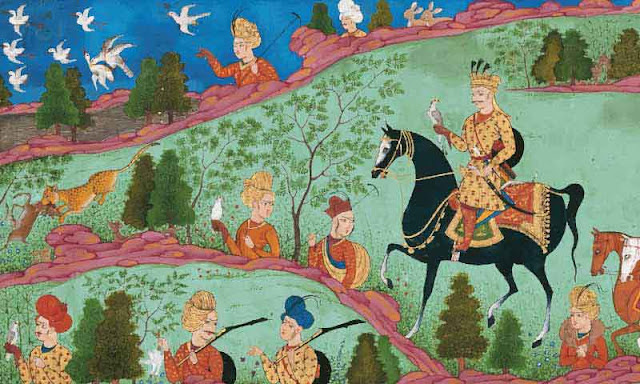

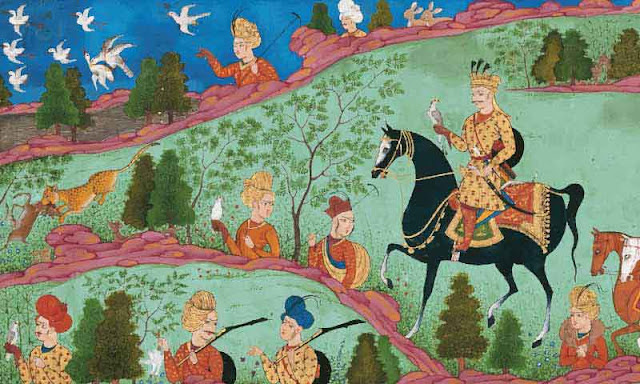

| Hindu King on horseback |

First King Rituparna rode forth on a fine white mare, which he called Storm. He was dressed in fine silk cloths and his horse was decorated in Ayodhya’s greatest finery. The horses golden reins and tackle shined in the sun. Jivala was mounted on the fast grey stallion, Thunder. He was wearing the uniform of the king’s charioteers and his horse was decked with silver, the reins fastened tight.

King Rituparna smiled and waved at the crowds gathered there. The townspeople and men of the court cheered their champion. He brought his horse to the line.

Jivala held the reins closely on Thunder. He trotted to the line. A few ladies cheered him from a distance.

Just as the race was about to begin, the crowd broke into laughter. King Rituparna turned to see what the scandal was all about. He could see his hunchbacked horsemaster mounted on Blaze, trotting to the line.

It was a ridiculous sight. The hump-backed dwarf, with his hooked nose, coal black beard and strange garb was riding bare-back, his raven hair wild in the wind. He stood up on the horse’s back, waving at the crowd, and flipped in the air. The crowd went wild at the dwarf’s equestrian antics. As a clown, he was a great success. But in a race with royalty? Blaze didn’t even have a saddle. How could he hope to compete with the king?

He reached the line. King Rituparna looked at the pitiful dwarf mounted on the wildest horse in the stable. “Where’s your saddle?” He said. “I never heard of a race without a saddle.”

“Long ago, in the land of the mlecchas, I learned to ride without a saddle. In the sands of the deserts where the camels roam, the nomads ride bare-back. As your horse-master I should be considered as a candidate for this race.”

The King smiled, “What shall be the stakes?”

“Friendly stakes,” said Vahuka. “I’m tired of the soup you serve around here. I have a mind to show my skill at cooking. If I win, you make me head of your kitchen.”

The horses stamped their feet. Jivala held the reins even tighter. The king laughed. “A horse-master chef? I hope your soup doesn’t smell of the stables.”

The minister of war held a silk handkerchief high in the air. When it fell to the ground the race would begin.

“Very well, Vahuka,” he said. “Take care with that horse. He has a deadly character.

The war minister raised the handkerchief still higher. They readied the horses for a charge. Blaze, Thunder, and Storm tensed the large muscles in their necks. Their eyes bulged.

|

| Horse Race, Greek Urn |

The silk handkerchief was in the air. The reins tightened. King Rituparna’s horse Storm shot off down the field, his hooves shaking the earth. Dust flew. Jivala was next on Thunder. Blaze trotted down the field. Vahuka smiled peacefully, standing on the horses back and waving to the crowd. The stallion stopped and reached down to taste a flower, unconcerned as the two royal horses sped down the racecourse.

Rituparna had put quite a distance between his own Storm and Jivala’s Thunder.

As they turned the first corner, Vahuka sat down and stroked the horse’s mane, fondly. “Run like the wind," he whispered in the horse’s ear.”

Suddenly Blaze bolted into action. His head went horizontal, his teeth were gritted, his eyes showed white. He seemed to fly above the earth. He charged, his hooves thundering over the turf, as he carried the dwarf Vahuka just as the wind carries a leaf.

Jivala felt a rush of air as Blaze raced past, nostrils flared. The dwarf smiled at him as he pulled even tighter on the reins. He wanted to reach for the whip, but the whip had been banned.

But Vahuka needed no whip. He whispered again to Blaze as they rocketed past Jivala on Thunder.

King Rituparna was still far ahead, nearing the finish line. Some of the crowd cheered the king, but others began cheering the dwarf who was closing. Jivala was far behind as Blaze kicked up the dust.

As they came into the final turn, Rituparna smiled. It would be an easy victory. The brahmanas would be happy with their new cows. He could hear the crowd cheering him on.

As they came into the stretch, Vahuka on Blaze was inching up on Storm. Both horses were straining to run as fast as they could, but Blaze was running without the weight of a saddle, without the chafing of the bridle, and his rider ran without the restraints of a king’s rich garments. Leaning forward, the dwarf whispered again. Blaze ran even faster.

Rituparna was shocked. “Who is this dwarf?” He thought, “Is he a Gandharva in disguise?” just as Vahuka raced past. He pushed Storm to respond, but the horse could run no faster.

In a trifle, the race was over. Vahuka rode Blaze fast as the wind to the finish line. King Rituparana arrived a full second later. They waited a bit for Jivala, whose horse Thunder was exhausted. The crowd cheered the victor. “Hurray for Vahula! Hurray for the Dwarf! Vahula ki Jai!” they shouted.

After the race, King Rituparna congratulated Vahuka and appointed him master of the kitchens. The following day, Vahuka prepared a great feast for all. Brahmanas were invited to the feast which was served at an auspicious hour. After an aroti ceremony offering everything to the Deity of Vishnu, all were served. They sat in the courtyard in the shade of a huge tamarind tree. There were rich subjis, simple rice dishes with saffron soaked in ghee or clarified butter. There were refreshing drinks and payasam, sweet rice. A large variety of fresh fruits, vegetables, and different kinds of savories, samosas, and pakoras were served, followed by a number of desserts. Everyone agreed that Vahuka was quite a cook.

Two of the brahmanas there had traveled from the court of King Bhima in Vidarbha. As they were eating, one of them said, “I have traveled far and wide in the kingdom of Ayodhya and have never seen anyone with such skill at horses.”

His friend said, “There is only one man capable of such a feat. But alas, he was exiled to the forest by the cruel King Pushkar after losing everything in a dice game.”

The first brahmana laughed: “You must mean King Nala. Nala was tall with curly golden hair. This Vahuka is a clown. He may be good with horses but he has nothing in common with King Nala.”

His friend smiled as he licked a bit of buttery rice from his finger, “He has another thing in common with Nala. This saffron rice. I have only tasted rice like this once before; in the kingdom of Vishadha at the feast of Damayanti.”

“You're right my friend. It may be that Nala has come upon hard times and disguised himself. We must return to Vidarbha and inform the King of these strange events.”

And after finishing their meal the two brahmanas excused themselves and set off on the road to Vidarbha and King Bhima.

Michael Dolan, B.V. Mahāyogi

Nala and Damayanti

The Stampede of the Wild Elephants

When she saw the caravan fording the river, downstream, Damayanti rubbed her eyes. Was this a dream? Would they disappear like the holy hermits in the enchanted forest?

They began to wade across. There were men dressed in the style of merchants, horses, asses laden with goods and bullock carts whose heavy wheels wore grooves in the mud. The men helped guide the carts across the river.

The water was only knee-deep at the ford. The reeds grew tall, and geese played on the waveless water. A few women carrying baskets began across, as the men with the carts reached the cane bushes on the near side.

Damayanti realized then that this was not a dream. For the first time in days she was close to civilization. These people would help her recover her Nala. She ran to them, waving her arms in desperation.

The men and women of the caravan saw a madwoman running toward them waving her arms. They shrank from the slender-waisted Damayanti. Half-clad in a torn sari she seemed like a maniac, thin and pallid. Her locks were all matted and covered with dust. Some ran in terror from this river spirit. Others approached her in pity and asked, “Who are you? Are you a spirit of this wood? Are you a yaksha or a rakshasa who protects these waters? If you are some divine god, bless us poor merchants who are on our way to market in the city of Chedi which lies through through these woods some leagues away.”

And Damayanti said, “I am only a poor girl who has lost her way. I am the daughter of Bhima, king of Vidarbha. I am looking for my great husband, the king Nala, ruler of the Nishadhas, who has lost his kingdom and been exiled to the forest. Please tell me if you have seen him pass by here.”

Now, the leader of that caravan was a merchant man named Suchi. He said, “O queen, daughter of Vidarbha, we have seen no such man or king pass this way. We have marched for many a day through this forest and have seen neither man nor woman. Elephants and leopards haunt these perilous woods. We have seen buffaloes, tigers, and bears. But no men.”

“Good sir, tell me where you and your company are bound,” she said.

“We are heading for the city of Lord Suvaha, the honest and truth-telling king of the Chedis. Join us, for we shall take you back to civilization through this dark and terrible forest. This is no place for a young and beautiful girl such as you.”

They made camp for the night on the banks of that placid stream. Damayanti bathed, and was given fresh cloth by some of the women of the merchants. And after eating a hot meal in the company of the ladies there, she rested. On the following day, Damayanti joined the caravan’s march as they went through the forest on the way to Chedi.

After a three day march, they left the dark and awful forest and arrived at the shores of a great lake, covered with lotuses. All around the lake were unusual flowers, bamboo and sugar cane.

The water of the lake was crystal pure and refreshing. There was plenty of grass for the horses and oxen, and plenty of sweet sugar cane. It was a natural oasis of fruits and flowers, coconuts and bananas, lotuses and kadamba flowers. Melodious birds filled the air with song.

Their leader, Suchi, signalled to make camp there. And they found delightful shelter in that pleasant grove.

But that land was the favorite of the elephants. And as they slept, a group of wild elephants came from out the forest and began to run to the lotus-filled lake to drink and bathe themselves and to feast on the sugar cane.

Those mighty beasts ran right through the pleasant groves where the caravan lay sleeping. And as the merchants arose and tried to defend themselves, waving their arms and screaming, there the elephants panicked.

The elephant herd charged and stampeded, crushing horses and camels; and in their wild rampage they killed some of the merchants with their tusks and others by trampling.

Some of the merchants ran in terror only to be trampled. Others climbed trees to escape the charging elephants who did great destruction to the caravan and to their camp.

Some uttered cries of terror as they were crushed beneath the powerful legs of the mad elephants.

In the chaos, some men drew swords and spears. They threw their spears at the elephants, killing other men.

And so it was that the caravan that had rescured Damayanti suffered great loss on account of the elephants. The campfires were overturned. The flames became a raging fire burning through the sugar cane. And the conflagration reached even the men who had hidden in the trees. And there arose a tremendous uproar like to the destruction of the three worlds at the end of time.

In the morning the elephants had gone. And some of the more unscrupulous followers of the caravan had gathered the jewels and gold of the others and made off with their wealth, fleeing the camp. Others merely fled the frantic carnage, returning to the river from whence they came.

And as the sun came up, those who were left behind wondered much at these occurrences saying, “Such misfortune has never befallen us before. Perhaps we have offended some spirit of the forest.”

Envious tongues blamed Damayanti, saying, “Yes. We were fine before that madwoman arrived. She must be a Rakshasa, or some other supernatural being or a demon sent from hell to torture us.”

When she awoke, she could hear the others talking. Damayanti took shelter behind a tree and listened as the others conspired against her.

“This demon-girl is bad luck. We should kill her,” said one.

“She must be a Rakshasa who bewildered our leaders with her beauty. But she must be stopped before her magic kills us all..”

One of the elders who had survived said, “She should be stoned to death. Or left to be trampled by the elephants.”

Another said, “She must be drowned in her own lake. Or beaten to death with our very fists, the she-devil.”

An old woman said, “Who is this woman? She brought evil upon us. Did you see her maniac eyes, her barely-human form? She is a witch whose black magic has cursed us all to death. Who else but a demon would cause us harm. Let us set upon her with stones and bamboo sticks. We must put her to death or perish ourselves.”

In terror and shame Damayanti fled to the shade of the forest. There she found a path that wound around the other side of the lake where there were no flowers but only brambles and thorns. Her bare feet bled to step on the rocky path.

“Why am I so cursed? Could the gods be so angry with me? What was my sin? I scarcely met this host of men when they were slaughtered by mad elephants. But my accursed life was spared, that I might spend more time in sorrow. No one dies before his time, they say. And what befalls us, good our bad is our own destiny. And yet, even as a child I never did anything so sinful as to cause such a terrible reaction. I must have offended the gods at my swayamvara. I rejected them for Nala. Perhaps had I chosen a god for my husband, I wouldn’t find myself lost in this terrible forest. But how could I have chosen otherwise. Nala was my destiny.”

And so, lamenting her fate, Damayanti walked on towards the sunset. And as she came over a small rise in the footpath, she could see, shining in the distance the stone towers of the city of Suvahu the truth-seeking king of the Chedis. At last.

नारायणं नमस्कृत्य नरं चैव नरोत्तमम्

देवीं सरस्वतीं चैव ततो जयम् उदीरयेत्

Michael Dolan, B.V. Mahāyogi

Nala and Damayanti

The Magic Dwarf:

"Where has she gone?"

Brihadaswa said, “Late at night, Jivala was passing by the stables. He could see the light of a candle flickering through a window. He approached and heard the plaintiff sound of a lute, accompanied by a low, gruff voice. The dwarf was singing.

Curious, Jivala came closer to the window. He could see the dwarf playing a curious musical instrument. As he listened, he could hear Vahuka sing a sad and original ballad about a king who loses his empire. “What a strange song,” thought the king. He walked to the door of the stables and entered quietly, but As he approached, the dwarf stopped singing and put down his lute.

“Vahuka,” said the Jivala. “Don’t stop. I just came to sweep up the stables. I must confess, you have surprised us all. I never thought you would outrace the king of Ayodhya. And all the royal guests at court are satisfied. The brahmanas there have never tasted such rich food. Your feast was quite a success. And they’re all talking about the horse race. I must say, you’ve made quite a reputation here in Ayodhya, my dear little dwarf. And now it turns out you play the lute. I’m sorry to interrupt, you sir. Please continue your song.”

And Vahuka the dwarf looked at his friend Jivala. He picked up his lute again. He said, “Very well, my lord. I’m not much of a singer. But my song tells an old story. Perhaps you’ve heard it before. And he sang Jivala a strange ballad of a far off kingdom where a great and noble king ruled. He was married to a fair princess, who had chosen him from among the gods.

He ruled peacefully for twelve years, but one day, the king broke ekadashi. and fell under the influence of a demon, Kali. Possessed by the demon he played at dice and lost his kingdom. Exiled to the forest, he abandoned his wife, was bitten by a snake-prince, and became an ugly dwarf, bound to train horses.

When he finished Jivala was astonished. “What could it mean?” he though. “Was Vahuka telling his life in song? Was he accursed or possessed by some strange demon?”

“That’s a strange song,” he said. “And so sad. Is this your composition?”

Vahuka smiled. “Like most sad ballads, this one tells an unbelievable story, and yet it reminds me of someone and the melody is not without merit.”

“But you have traveled far and wide,” said Jivala, suspecting that Vahuka wasn’t telling the whole story. “Have you ever known anyone like this king who wagered his empire at dice?”

“Such things only happen in ballads, my friend” said the mysterious dwarf. He smiled widely, showing his broken teeth between his coal black beard as he slipped the ivory plectrum between the strings and put up his lute. “I’m glad the people enjoyed the feast. What does his lordship like for breakfast?”

“It’s such a sad ballad. There must be some truth in it,” said Jivala who stood in the stable doorway, leaning on his broom.

“Well, according to the poets, the sweetest songs sing of the saddest things.”

“Yes, but the song seems personal to you. What about the dwarf?”

“Oh, the old ballads are filled with dwarfs and dragons, Nagas, yakshas and rakshasas. You mustn’t take these things seriously. Surely they have been made up by poets to scare children into going to bed early. There are many such songs.”

“Do you know any others?” said Jivala.

“Oh, all right. If you like,” said the dwarf. He picked up his lute and took the plectrum from the strings. And once again he began to play and sing:

क्व नु सा क्षुत्पिपासार्ता श्रान्ता शेते तपस्विनी ।

स्मरन्ती तस्य मन्दस्य कं वा साद्योपतिष्ठति ॥

kva nu sā kṣutpipāsārtā śrāntā śete tapasvinī |

smarantī tasya mandasya kaṃ vā sādyopatiṣṭhati ||

“Where is she, worn and weary? Where is she, hungry and thirsty and torn by penance. Where does she rest?

Does she remember the fool who left her? And who is she serving now? O where has she gone?”

And Jivala said, “Who might be the lady’s husband?”

“The song tells of a man who lost his sense. The lady is faultless. But this fool leaves her, possessed by ghosts. And so he wanders, racked by sorrow.

"The wretch made false promises. He cannot rest by day or night. And so at night, he remembers her, singing this song, ‘O where has she gone?’ You want to hear the rest?”

“Play on,” said Jivala.

And taking up his theme again, Vahuka sang,

“Having wandered the whole round world, the wretch can’t sleep at night.

His soul possessed by Kali, his mind consumed with fright.

He broods and sings this verse of grief, it gives him some relief.

‘O where O where has my lady gone; he left her like a thief

Abandoned in the forest dark, the forest lone and dread.

O where O where has my lady gone? Alive? Or is she dead?

Dead to the love that we once had, lost to beasts of prey?

O where has she gone, where does she roam?

Her lord has gone away.’”

From Mahābhārata 3.64.9–19

11 evaṃ bruvantaṃ rājānaṃ niśāyāṃ jīvalo 'bravīt

kām enāṃ śocase nityaṃ śrotum icchāmi bāhuka

12 tam uvāca nalo rājā mandaprajñasya kasya cit

āsīd bahumatā nārī tasyā dṛḍhataraṃ ca saḥ

13 sa vai kena cid arthena tayā mando vyayujyata

viprayuktaś ca mandātmā bhramaty asukhapīḍitaḥ

14 dahyamānaḥ sa śokena divārātram atandritaḥ

niśākāle smaraṃs tasyāḥ ślokam ekaṃ sma gāyati

15 sa vai bhraman mahīṃ sarvāṃ kva cid āsādya kiṃ cana

vasaty anarhas tadduḥkhaṃ bhūya evānusaṃsmaran

16 sā tu taṃ puruṣaṃ nārī kṛcchre 'py anugatā vane

tyaktā tenālpapuṇyena duṣkaraṃ yadi jīvati

17 ekā bālānabhijñā ca mārgāṇām atathocitā

kṣutpipāsāparītā ca duṣkaraṃ yadi jīvati

18 śvāpadācarite nityaṃ vane mahati dāruṇe

tyaktā tenālpapuṇyena mandaprajñena māriṣa

19 ity evaṃ naiṣadho rājā damayantīm anusmaran

ajñātavāsam avasad rājñas tasya niveśane

|

11 एवं बरुवन्तं राजानं निशायां जीवलॊ ऽबरवीत

काम एनां शॊचसे नित्यं शरॊतुम इच्छामि बाहुक

12 तम उवाच नलॊ राजा मन्दप्रज्ञस्य कस्य चित

आसीद बहुमता नारी तस्या दृढतरं च सः

13 स वै केन चिद अर्थेन तया मन्दॊ वययुज्यत

विप्रयुक्तश च मन्दात्मा भरमत्य असुखपीडितः

14 दह्यमानः स शॊकेन दिवारात्रम अतन्द्रितः

निशाकाले समरंस तस्याः शलॊकम एकं सम गायति

15 स वै भरमन महीं सर्वां कव चिद आसाद्य किं चन

वसत्य अनर्हस तद्दुःखं भूय एवानुसंस्मरन

16 सा तु तं पुरुषं नारी कृच्छ्रे ऽपय अनुगता वने

तयक्ता तेनाल्पपुण्येन दुष्करं यदि जीवति

17 एका बालानभिज्ञा च मार्गाणाम अतथॊचिता

कषुत्पिपासापरीता च दुष्करं यदि जीवति

18 शवापदाचरिते नित्यं वने महति दारुणे

तयक्ता तेनाल्पपुण्येन मन्दप्रज्ञेन मारिष

19 इत्य एवं नैषधॊ राजा दमयन्तीम अनुस्मरन

अज्ञातवासम अवसद राज्ञस तस्य निवेशने

|

Nala and Damayanti:

Damayanti Reaches the Kingdom of Chedi

Damayanti walked all night, and all morning in the sun, until finally she arrived in that city of vast stone towers painted gold. Disturbed, emaciated, covered with dust, her hair tangled, and her dress torn, Damayanti hardly looked like a queen. The street urchins began to follow her through the streets and tease her, calling her names. “Maniac!” they cried, and “madwoman!” Snarling dogs nipped her heels and barked. On she walked, past the markets with their colorful tents and banners. The city boys followed, throwing stones at her. And circled by this throng of dogs and boys, she staggered to the palace gates.

At this time, the Queen Mother was watering her roses in her terrace atop the lofty palace rooftops. As she plucked a weed, she heard a noise below her.

“What is it?” said she to her lady-in-waiting. “Is today a festival day again? Why are the people creating such an uproar?”

And her lady-in-waiting looked out over the rampart walls.

Damayanti had fainted. The boys pressed around her, delighted with the fun as they tormented her with name-calling. The dogs became more animated and leaped into the air with canine joy.

Damayanti lay unconscious before the gates of the palace of King Chedi.

The Queen Mother snipped a wilted blossom from the rosebush. Joining her lady-in-waiting at the rampart walls, she looked down to the public square before the palace.

The Queen Mother saw a scandal of barking dogs and dirty boys laughing at the half-clad madwoman fallen at the gate. And from her tower high above the city, she called down to a guard. “Stop this scandal! Dismiss that mob at once. Help that lady to her feet.”

The guard, who had had been watching the boys, stepped forward with a fierce look, his strong right hand on his sword hilt. The boys could see he was serious and ran away in glee, taking the dogs with them. He went to Damayanti.

The Queen Mother told her hand-maid, “Go down and bring that woman to me. Bring her to me. I wish to know who she is.”

“Perhaps she is only a madwoman,” said the hand-maid. “It may be dangerous to bring her here.”

The Queen Mother said, “Yes, she appears to be a madwoman and a maniac, but there’s something about her that tells me she is special. I have never seen her in the village. By her dress, she comes from far away. And her lotus eyes tell me she must be from a royal family. Even disguised as a half-naked madwoman, she seems to me like an angel from heavean. Please, go down and bring her to me.”

And so the maids of the Queen Mother went down the marble stairs of King Chedi’s palace. And when the arrived at the front gate, they found Damayanti still unconscious in the care of the royal guards.

With a potion made of herbs they revived her. And taking he by the hand they said, “Come with us. The Queen Mother would have audience with thee.”

And so they ascended the palace stairs to the tower above the city of King Chedi, where the Queen Mother kept her roses on the rooftop terrace.

And when they arrived, Damayanti was given a fine sitting place befitting a princess of royal blood. The maids brought her a refreshing drink made of rose-water and cooled her brow with a cloth moistened with lavender.

The Queen Mother said, “Who are you, child? While worn with distress, half-clad in rags, and covered with dust, your beauty shines like lightning through dark stormclouds. Your form is more than human. While you wear no jewelry or ornaments, still you have an almost transcendent loveliness, as if you were the bride of a god. Are you a goddess fallen to earth with some purpose for the king? Or an apsara come to bless our people and free us from some dark curse?

And Damayanti told her story: how she was born as the daughter of King Bhima in the realm of Vidarbha where once Sita held court; how the gods had wanted her as a bride; how she had chosen Nala, and the misfortune that had befallen her when Nala had gambled away their kingdom. She told her how Nala had abandoned her in the forest after taking half her garments, how she had wandered through the forest and met the wise men and the caravan, and how the mad elephants had broken up the caravan.

Damned by the gods for her beauty

“Perhaps I have been damned by the gods for my beauty,” she said. “When I did not take them as my husband, they were angry and have cursed me. You are kind, but it will be dangerous for you to give me shelter. The curse of the gods will follow me wherever I go.”

But the Queen Mother was kind and said, “Stay here with me, child. What you say is interesting, but I cannot believe that one so fair as you has been cursed by the gods. My men will find your husband. I don’t believe that one so fair as you has been cursed by the gods. Stay here for a while. We shall announce to the world that you have arrived here and your husband will surely come here and find you.”

“You are kind,” said Damayanti. “I will stay if you insist. But I have a few conditions. I will not eat leftovers from any plate or wash anyone’s feet. I will not speak with any man, and none shall seek me as their wife. Any man who harasses me again and again to be his wife shall be put to death. This is my vow. Also I need to speak with those forest sages who promised I would reunite with my husband.”

And the Queen Mother agreed, saying, “So be it,” and called her daughter Sunanda.

Sunanda was the Crown Princess, sister to King Chedi himself. And the Queen Mother said, “Sunanda, please accept this goddess-like lady as your personal companion. She comes from the land of Sita-devi herself and is paying us a royal visit.”

And the Queen’s daughter Sunanda welcomed Damayanti into her own apartment with her associates and hand-maids and accepted as her personal friend, showing her all respect.

And in this way Damayanti lived in the court of Suvahu as the personal friend of the lady Sunanda for some time.

Damayanti is Discovered: She Returns to Vidarbha

One by one the brahmanas arrived in the kingdom of Vidarbha for the feast given by King Bhima. The came from all corners of the kingdom. And when the ceremony was finished, the king spoke to the gathered brahmanas, “Who here has news of my daughter, the fair Damayanti? If anyone has any news of her whereabouts, consult with my ministers after prasadam.

Later that evening, the two brahmanas who had been at the feast of Rituparna after the race came forward. In a confidential meeting with the king, they told him of the fantastic dwarf with his amazing powers and of the fine saffron rice he had served. “I’m not sure if this helps,” said one, “but I’m sure this dwarf Vahuka has something to do with Nala.”

The king thanked the brahmanas and gave them cloth and silver in charity. He had heard from his spies that the body of a hunter had been found dead, mysteriously killed in the jungle were he had been hunting, not far from where Nala and Damayanti were last seen.

Others had brought him rumours of a strange prince, Karkotaka, who had been cursed by Narada to live immobilized in the forest as a snake. He had been freed from the curse and had returned to rule his kingdom. Among the rumours was the idea that Nala had redeemed him from the curse of Narada.

Could it be that his son-in-law, Nala was hiding in disguise? Perhaps his disguise had something to do with this famous dwarf, who now kept horses in the kingdom of Ayodhya. What an outlandish idea. But stranger things had passed in the kingdom of Vidarbha.

Ancient Gold Coins of Vidarbha, circa 800 BC

But where was Damayanti? There was no news of his daughter. The king rewarded the brahmanas richly and renewed his call for news.

The moon changed and went through its seasons. Summer came and went. The brahmanas searched far and wide for Damayanti.

Then, one day, a brahmana named Sudeva arrived in the kingdom of Chedi. And there within the kingly palace he remained for some time as a guest.

One evening as the brahmana was at prayer, worshiping the Lord Vishnu with the holy mantra as the sun disappeared over the Vindhya mountains, he saw one of the companions to the Queen Sunanda, glowing golden as the sunlight shining feebly through the dimness of a cloud.

Damayanti Forlorn, Raja Ravi Varma, Victorian India

As he finished his prayer he followed her with his gaze. He thought it must be the erstwhile princess of Vidarbha, but the large-eyed princess was dull in her beauty. She seemed wasted by grief and worry. And yet he felt it must be she.

“Could it be that Bhima’s daughter might be found here, gracing the court of King Chedi as the companion of his Queen Sunanda?” he thought. “King Bhima is almost dead from worry. I must know for sure.”

He couldn’t help himself and fixed his stare on Damayanti. The fair Sunanda, the Queen, entered. They joined arms and walked through the royal gardens. In the evening light, Damayanti appeared like the moon, darkly beauteous with her fair and swelling breasts, her lotus eyes wide.

She seemed like a lotus that had been plucked up from Vidarbha’s pleasant waters and set down in the royal gardens of Chedi, slightly wilted, covered with dust; She was like the dusty rays of moonlight which tremble with fear after Rahu has swallowed the darkened moon. Her beauty was like a dry stream waiting for rain, or a pool where the lotuses have wilted after the birds have fled. Or like a lotus which is parched after the pool dries. The sun burns the lotus after the water has dried; so seemed Damayanti without Nala: widowed from the joys of love, she was forlorn and melancholy.

Her light had dimmed. Forsaken by her husband, her beauty no longer shined as before.

“And where was Nala?” the brahmana thought. “While Damayanti is the fairest of all the land, sought after even by the gods themselves, her beauty has somehow faded. Joyless, stunned by loss, she wanders here in Chedi, mourning Nala. Was he killed in the dark forest? Or does he wander, possessed by ghosts or devils in that vast wilderness of lions and bears, forgotten, banished, and exiled?”

And thinking thus, the brahmana approached the Queen, Sunanda, and her royal companion, saying, “Dear Ladies, please excuse me. I am a humble brahmana.”

And Sunanda, ever respectful of brahmanas said, “Blessed be the humble, good sir.”

“My blessings upon you both,” he said. “Allow me to introduce myself. My name is Sudeva, and I come from the land of Vidarbha.”

Hanuman, Rama, and Sita Devi. Sita Devi was from Vidarbha.

Damayanti blushed to hear the name of her father’s kingdom and bowed her head.

“King Bhima has sent me here in search of his lost daughter Damayanti, who followed her husband Nala into exile so long ago.”

Sundanda’s face brightened, but Damayanti suspected a trap. She lowered her eyes and and covering her head with her sari held Sunanda’s arm tightly in her grasp. She whispered, “Sunanda: Remember the death sentence. What if this brahmana has been sent by Pushkara?”

The brahmana, who had overheard this exchange said, “Trust me, for I am honest.” And retrieving a ring from the folds of his garment, he said, “Look. King Bhima gave me this ring and told me to show it to the one who looks like Damayanti. My dear lady. I knew you when you used to run in the royal gardens of Vidarbha. I once saw you playing with a golden swan. I’m sure you must be Damayanti. Look, and see if this is your father’s ring and if I am honest.”

Her blush turned pale. She stepped forward and took the ring from the old brahmana’s leathery hand.

“Your father is dying of worry,” said the brahmana, “but your little girl, Indrasena, is fine and Indrasen your son grows stronger and healthier every day. For your sake hundreds of brahmanas like myself are combing the earth, searching for a sign that you are alive.”

Damayanti took the ring in her hands. The memory of her father brought color back to her cheeks. She returned the ring to the old brahmana. She uncovered her head.

“Forgive me for not recognizing you at once, dear Sudeva. Of course. It’s been a long time,” she said, folding her hands and offering respects. She smiled. Standing closer, Sudeva could now see her natural beauty returning. Just as the mountain stream is regenerated by the monsoon rains, Damayanti became more radiant, thinking of her children and her father at home in Vidarbha.

Sunanda invited them to sit. And there in the royal gardens they conversed. Damayanti asked a thousand questions of Sudeva, who was a great friend of her brother. She asked about her children and King Bhima and the ladies of the court as the wise Sudeva listened and gave her counsel.

And as they talked, Sunanda discreetly dismissed herself and went to see the mother of the king of Chedi. Sunanda told the queen mother, “A brahmana has come from the court of Vidarbha. Come and see.”

Soon the Queen Mother left her inner chamber and went to where the mysterious companion of Sunanda spoke quietly with the wise old brahmana.

And the Queen Mother asked Sudeva, “This girl has told me a strange and wondrous tale of kings and princes and exile. We found her wandering like a vagabond, a madwoman, tormented by wild children and dogs. And seeing that she had something noble in her, we have given her shelter here in our court. Do you know her? How much of what she says is true?

Nala and Damayanti in the forest

To which Sudeva said, “I have had the fortune to know the monarch of Vidarbha, Bhima, who is always generous to humble brahmanas. There, on occasion, I have given counsel to that great king. This lady here is Damayanti, the daughter of King Bhima, princess of Vidarbha. I recognize her by the beauty mark on he forehead. I have known her since she was a child, playing in the court of the king. Her husband is the King of Nishadha, Nala, son of Virasena. Nala was cheated of his kingdom by his envious brother, Pushkar, who gamed him at dice. When Nala was exiled, the faithful Damayanti followed him into the forest. We have been searching for her ever since. You have saved her from death by starvation. May Vishnu bless the piety of your soul.”

The Queen Mother could not restrain her tears and held Damayanti close to her. “Then you are my own sister’s daughter,” she said. “Your mother and I are both daughters of King Sudaman of Dasharna. We separated long ago, when she married King Bhima and I married King Virabahu. And now I remember you, my child. It was in my father’s home in Dasharna. My sister, newly wed to Bhima, came to visit. You were just a baby at your mother’s breast. How could I have recognized you, all grown up?”

To which Damayanti replied, “No one has been as kind to me as you. You took me in, thinking me a stranger, but looked after me as if I were you own daughter. There is only one place in the world more pleasant than your fine palace here in Chedi, and that’s my own home in Vidarbha. And now that it is safe for my return, please, O Queen Mother, give this poor banished woman leave to depart for my home. I would return home were my infant children long for my return. They haven’t seen their father Nala in so long, but perhaps if I am there, I can give them some comfort. O Sudeva, thank you. You have given me new hope. Let us go to Vidarbha.”

And the Queen Mother, tears of joy in her eyes, said, “So be it, my daughter.” And she called to the guards: “Let the palanquin be prepared. Go forth to Vidarbha!”

Brihad Aswa said, “And so it was that a splendid palanquin was prepared for Damayanti. Eight strong men carried the royal palanquin over the Vindhya mountains guarded by a mighty army. And as she was born aloft, she was well-provided with fine cloth, refreshing drink and delicious food.

Return to Vidarbha

And by and by the princess returned to Vidarbha, where the earthborn Sita herself had once ruled. The citizens of Vidarbha rejoiced and chanted the Vedic mantras to see her return. And there she found her kinsmen in good health. Indrasena and Indrasen ran to her bosom and held her close as Damayanti’s tears blessed their foreheads.

Then King Bhima embraced his daughter and smelled her head. He too cried tears of joy and smothered Damayanti in his long white beard. The king declared a festival holiday and rewarded the old brahman Sudeva with a thousand cows, land for their pastures, gold and silver, and a temple for the worship of Lord Vishnu. And everywhere the land rejoiced at the return of their daughter and princess, Damayanti.

When all had retired and the night was peaceful, Damayanti’s mother came to her.

Damayanti abandoned in the forest

And when they had talked long into the night, after Damayanti had told her of all her trials in the forest, at last she said, “I am so happy to see my children again. But if I am to live, it will be a barren life without my Nala. If you love me mother, do what you can to see that they find Nala. Let it be your chief toil to find the hero Nala and bring him home. This is all I ask.”

At which the honest Queen could give no answer, for she was sure that Nala was forever lost. Her face clouded, she could not restrain her grief. “O, Damayanti,” she said, “Ask me anything, but Nala I fear is lost.” And at this both mother and daughter wept in sorrow, and so they passed the night.

The Song of Damayanti

As the sun dawned through the Ashoka trees in the royal gardens of Vidarbha where Damayanti once saw a swan messenger, the Queen left her sleeping daughter and made her way to the inner chambers of the King.

“What news?” said he. “Is our daughter refreshed after her arduous ordeal?”

“She is sleeping,” said the Queen. “But she mourns the loss of Nala. As she wept, she broke her silence and told me we must search for him.”

King Bhima frowned, “Ah, but Nala died in the forest long ago. I have sent brahmanas to search high and low for him. We have heard nothing these many months. How could it be possible for such a great king to abandon his wife. No, Nala must be dead.”

“We must try again,” said the Queen. And so once again Bhima called the brahmanas to his court. “Please speak to my daughter,” the king said. “She is inconsolate.”

At this time young Damayanti approached the assembled brahmanas and spoke as follows:

“My dear holy fathers. I believe Nala is alive. I believe he has disguised himself to avoid a sentence of death passed by his cruel brother, King Pushkar. Do not ask for Nala openly.”

And one of the brahmanas said, “How shall we proceed, my lady? We are honest brahmanas, always direct. By what means shall we ask for news of Nala?”

To which the princess of Vidarbha replied as follows: “You must speak in carefully. In every realm go forth to places where men gather. In every gathering repeat these words again and again:

९ क्व नु त्वं कितव छित्त्वा वस्त्रार्धं प्रस्थितो मम

उत्सृज्य विपिने सुप्ताम् अनुरक्तां प्रियां प्रिय

१० सा वै यथा समादिष्टा तत्रास्ते त्वत्प्रतीक्षिणी

दह्यमाना भृशं बाला वस्त्रार्धेनाभिसंवृता

११ तस्या रुदन्त्या सततं तेन शोकेन पार्थिव

प्रसादं कुरु वै वीर प्रतिवाक्यं ददस्व च

(Mahābhārata Book 3. 68.9-12 )

kva nu tvaṃ kitava chittvā vastrārdhaṃ prasthito mama |

utsṛjya vipine suptām anuraktāṃ priyāṃ priya ||

sā vai yathā samādiṣṭā tatrāste tvatpratīkṣiṇī |

dahyamānā bhṛśaṃ bālā vastrārdhenābhisaṃvṛtā ||

tasyā rudantyāḥ satataṃ tena śokena pārthiva |

prasādaṃ kuru vai vīra prativākyaṃ dadasva ca ||

“Where have you gone, you gambler, my king?

You abandoned me when I was sleeping.

You tore my dress and vanished, my love.

You left me asleep in the forest, my love,

Alone, abandoned and lost.

Where have you gone, now that you’ve left me?

She sits and waits as you ordered;

Tortured by sorrow and loss;

Constantly weeping with sorrow, my king.

Have mercy and come back to me.”

"Recite this poem in the assembly of men, wherever they gather." She said, "And add this:

“A wife should be protected; not abandoned and left all alone.

O noble hero, wherever you are, listen to my prayer. Just as fire should be tended carefully, so a wife should be cared for by her husband. Have you forgotten your duties, you who are so skilled in duty? It is said that kindness is the best of all virtues. Have you forgotten how to be kind?” You may add this, so that if Nala is alive, if he is in disguise and hears my message, his heart shall be pricked by compassion. Hearing this song, he will come out of hiding.”

“If anyone hears this song and comes forward, you must send me news. But be discreet. None should know that this message comes from the Princess of Vidarbha. But take care to learn everything about whoever understands the message. And return and tell me the news. Find out everything you can about the one who answers this call. For the man who answers my message will surely be Nala Himself.”

Nala leaves Damayanti

And so addressed, the brahamanas once again went forth to help the forlorn Princess of Vidarbha. They went far and wide to all the realms surrounding the kingdom. They went to Ayodhya and Vishadha and the valleys of the Vindhya mountains. They passed through cities, towns, villages, hamlets, places inhabited by cowherds and the retreats of hermits in the woods. And wherever they went they sought the lost King Nala. And everywhere they went they recited the song of Damayanti just as she had taught it to her.

The Search for King Nala

After a long time had passed away, a brahmana named Parnada returned to the city of Vidarbha. The old wise man sought audience with the Princess. And when she came out, he bowed before her and said, “O best of women, I have some news which may interest you.”

And the daughter of Bhima said, “Please speak. I’m eager to hear you.”

Parnada said, “ While traveling through the realm in search of your lost husband, I came to the city of Ayodhya. There I met the son of Bhangasura, whose name is Rituparna. He is the ruler of Ayodhya. I followed your instructions and repeated your words. No one there took any interest in anything I said, although I repeated your words several times. Neither the King, nor his courtiers, nor any of the men there answered anything. I’m sure they felt I was composing some poetry.

“Then, after I had been given leave to go by the King, I was approached by a strange man in His Royal service. This man is a kind of charioteer or horse trainer by trade. His name is Vahuka. It’s hard for me to believe that this Vahuka is the man you seek. He is, you see, a dwarf. A dwarf of hideous countenance whose twisted visage and hooked nose is marred by a coal black beard. And yet, he is a man of many accomplishments. Not only does he keep the king’s horses, but he has trained them to run at great speed. He is a master of the culinary arts and often prepares the King’s feasts.”

In any case, this dwarf Vahuka approached me as soon as I had finished. And as I was leaving, he held my arm in his rough grip. He took me aside. And as he wiped tears from his cheeks, he spoke to me in a choked voice.

"He said, ‘Your song has moved my heart. You have composed well. It grieves me to hear how a noble woman was abandoned in the forest with only half a garment. And yet still she awaits the return of the gambler King. This is good.’

‘A chaste women, although fallen into distress, will yet protect her virtue,’ said the dwarf. ‘ Even though they may be abandoned by the King they do not become angry on that account. A chaste and faithful women leads her lives protected by her honor. She will wear her virtue like a silver suit of armor that protects her from all harm. A woman who shows such self-control may gain mastery over the universe and even reach heaven itself.

“‘And yet the lady in your song should not be angry with this gambler king. Robbed of all fortune and even stripped of his garment by thieving vultures, he must have left her to her fortune that she might live.

“‘Because, if this lady had followed her gambler King into the dark forest she would surely have perished along with him. Knowing that her husband has suffered so, should not be angry even while forsaken. I’m sure your gambler King poem was too overwhelmed by sorrow to return to his lady. If he could, that gambler King would surely return to her side. But his destiny is to hide in misery and exile, grief stricken, famine wasted, and worn with woe.’

“‘A noteworthy composition. I am deeply moved. I wonder at the patience of the lady.” And saying this that shrunken dwarf let go his grip and vanished into the mist.’

“After I heard this mysterious discourse from the dwarf, I came her as quickly as I could,” said the wise old brahmana. “Perhaps this news may help your royal highness.”

Damayanti thanked the brahmana Parnada, gave him charity and sent him on his way. Tears came to her eyes to think that Nala was alive. But she had to be sure. She sent for her mother, and, swearing her to secrecy said, “My dear mother. I have had some news. But we must be discreet. For now, I can’t say anything. My father must not know anything of my plans. But I have an idea. If you at all wish to help me, please follow my instructions.”

“What is it child?” said the Queen.

“First we must send for that most discreet of brahmanas, Sudeva, who discovered me in the kingdom of Chedi. Only he may be trusted with my purpose. I want him sent to Ayodhya.”

“As you wish, my dear,” said the Queen and sent for Sudeva.

And when Sudeva had arrived, Damayanti said, “O best of the twice-born, only you can fulfill my purpose for it was you who found me in Chedi when I was lost to the world.”

Sudeva bowed deeply. He comforted her with sweet words and auspicious mantras and listened to her plan.

“Sudeva, I want you to go to Ayodhya and give this message to the king who rules there, Rituparna. Tell him these words exactly: ‘Bhima, King of Vidarbha, has issued a royal decree. As Princess Damayanti’s husband has disappeared, he is hereby proclaimed dead. The princess, having passed a long time of mourning and grief will offer her hand in marriage to the champion who comes and claims here. Let the word go forth to all challengers that Bhima’s daughter is holding a new swayamvara.

"All great kings and princes are gathering in Vidarbha for the occasion. The ceremony is to take place tomorrow. O King of Ayodhya, if it is possible for you, go at once to Vidarbha. After sunrise tomorrow she will choose a second husband, having given up Nala for dead.”

Sudeva was perplexed to hear these words, but said nothing for he knew Damayanti must have a deeper purpose.

Brihad Aswa said, “and so it was, my dear King Yudhisthira, that the wise old brahmana Sudeva set out on the road to Ayodhya.”

नारायणं नमस्कृत्य नरं चैव नरोत्तमम्

देवीं सरस्वतीं चैव ततो जयम् उदीरयेत्

महाभरत

Mahābharata

As retold by

Michael Dolan, B.V. Mahāyogi

Nala and Damayanti

Bridhad Aswa said, And it came to pass just as Damayanti had ordered. The wise old Sudeva went to Ayodhya and gave the news to King Rituparna.

Rituparna rewarded him and thought, “I have heard of the beauty of tis Damayanti. I shall compete for her hand. But I must hurry. There is no time at all. Her ceremony will be tomorrow and Vidarbha is several leagues from here. I will need fast horses.”

And so the King immediately went to Vahuka and said, “Ready the horses! It’s time to prove your skill.”

The dwarf brought out the king’s horses and said, “Where to, master?”

And as he arose on the chariot, King Rituparna said, “We need to hurry. The beautiful princess Damayanti has announced a new svayamvara. All great kings and princes will be in attendance. She will choose her suitor from among them. He will be the next king of Vidarbha who wins her hand. I intend to ride to Vidarbha in a single day. It’s quite a distance, but with your skill at horses we can make it.”

Brihad Ashwa said, “Imagine how Nala felt, my dear Son of Kunti.

“While King Nala had abandoned Damayanti, somehow he expected her to keep faith. It never occurred to him that she would find another. Even as he was still under the influence of Kali, his heart burned in sorrow. ‘How could Damayanti choose another?’ he thought. ‘Has she have given me up for dead?’ he thought. ‘Am I nothing to her?’

And so, Nala was determined to go to Vidarbha and see Damayanti. Could it be true that she would pick another prince? Or was it all just a ruse? And Vahuka selected four lean and muscular stallions. They were fresh and ready to run with wide nostrils and swelling cheeks.

But when the king saw them, he said, “These horses are quite lean and skinny. Are you sure they can run to Vidarbha in one day?”

“Notice the curl on the forehead? These horses were born in Sindhu and are fleet as the wind. Trust me. But if you see any others that you like better, choose them and I will take them instead.”

“You know best,” said the king.

Vahuka yoked the horses to the chariot, Vahuka the dwarf turned to Rituparna the king and said, “We’re ready. It’s a challenge to ride to Vidarbha in a single day. But we shall ride like the wind.” And so saying, he held the reins that the king could mount.

As the king mounted the chariot, he said,

“Ah but poor Nala died in the forest. Or how is it possible that such a great king abandoned his wife. No, Nala must be dead. And so young Damayanti has announced a new svayamvara. All great kings and princes will be in attendance. Who knows,” said Rituparna, smiling, “Even one such as you can compete. Let’s get a move on.” And so together they made ready their horses and chariot.

The king’s personal driver, Varshneya drove the chariot, but Nala soothed and guided the horses, using the divine mantras he had learned so long ago. As they flew across the plains the wheels barely touched the ground. The horses were fleet of foot and raced as they never had before. The king, Rituparna, was pleased.

But Varshneya had known Nala. They had often worked the horses together. And seeing the dwarf endowed with such skill in horses, Varshneya admired him in wonder.

’Who is this man?’ he thought. ‘He drives the horses as if he were Matali, the charioteer of Indra himself. This rough dwarf is the great horseman I have ever seen, with the exception of King Nala of Vishadha. Only the great Nala had such skill with horses. But Nala died in the forest and his widow is even now seeking a new prince. Could this be Nala? And if not Nala, then who? Sometimes the gods, disguised, wander among us. His deformity of body confuses my judgment. But they are equal in age. How could Vahuka know the same science as Nala? Perhaps Nala has been cursed to take this form. This Vahuka has all of Nala’s virtues, except appearance. But appearances deceive. He must be Nala,’ concluded Varshneya who had once been Nala’s driver.

The king himself admired the great of Vahuka who effortlessly guided the horses over mountains and rivers, woods and lakes. They flew like a bird at the speed of the wind; the chariot wheels barely touched the earth. And as they raced along, the king’s royal sash was carried away by the wind. He said, “O Vahuka, I dropped something just a moment ago. Let us return and pick it up.” But Nala in the form of Vahuka smiled and said, “Sire, your sash is far behind us now; we have gone a league since then. We may not turn back.”

And the king again wondered at the great skill of his horse-keeper and thought to himself, “Perhaps he can teach me what he knows.”

Now the king had great skill at mathematics. He thought, ‘Each one has his own knowledge; his is horses, mine is numbers.’ He could calculate the number of leaves on a tree by counting the branches. And so to impress Nala, he told him how many leaves and fruits were on a tamarind tree that they passed.

Nala stopped the horses. He lost his kingdom when his brother Pushkar cheated him at dice. His ignorance of mathematics had cost him dearly, and now he could see his redemption. He returned to the tree and carefully counted the leaves. “How is it possible that you have dominated the science of numbers so well?”

And the king taught him the trick, saying, “I know many things. If you like I can teach you. But in return I must learn from you how you dominate horses.”

Vahuka the dwarf said, “It may be easy if you know how. But this skill really eludes me. I would like to learn about the laws of probability and how to calculate odds at dice playing. I am not very expert in dice. In fact as a consequence of some bad bets I made, I am in the condition you see me now, reduced to poverty. Teach me about mathematics, dice, and the laws of probability, and I shall teach you everything I know about horses.”

They stopped along the road there and made camp for the night, for Vahuka was sure he could still make Vidarbha by sunrise. And all through the night, Nala taught the king the different mantras for controlling horses and the king taught Nala everything he needed to know to win at dice.”

By early morning, Nala had mastered mathematics and the art of throwing dice.

With this, Kali knew that at last he was defeated. He had suffered long with the poison of the Naga prince, but now he had lost control of Nala. He came out of his body, ending his possession of that miserable king, and vomiting the poison of the viper Karkotaka. And as Kali left the body of Nala, so did the curse that had caused him such great misfortune. And Nala, seeing his demon tormentor was about the curse Kali, who cowered before him.

But Kali, who was visible only to Nala said, “O King of men have mercy on this poor devil. When you abandoned Damayanti on my account, she cursed me. Since that time I have only known pain, scorched by the Snake-king’s poison. Spare me, and I will grant you a boon. Wherever men remember your name they shall be free of the influence of Kali. I am the demon of the iron age to come. Inspired by me, men will do awful things. They will rain fire from the heavens and scorch the earth. But those who remember how King Nala suffered at Kali’s hands shall escape my spell. Your name will be their refuge if you spare me. Do not curse one who begged for shelter at your feet.” And so saying, Kali split a Vibhitak tree and entered into it, becoming invisible.