नारायणं नमस्कृत्य नरं चैव नरोत्तमम्

देवीं सरस्वतीं चैव ततो जयम् उदीरयेत्

महाभरत

Mahābharata

As retold by

Michael Dolan, B.V. Mahāyogi

महाभरत

Mahābharata

As retold by

Michael Dolan, B.V. Mahāyogi

Notes on Mahabharata:

Dates, Editions, Narrators

Date of the Battle of Kurukshetra

There is some

speculation as to the actual date of the war described in the Mahabharata.

According to the ancient Hindu tradition since before the time of Alexander the

Great, the Mahabharata war coincides with the beginning of the Iron Age, the

Age of Kali, which marks a departure from the golden age of yore and a

considerable moral downfall as well. Many episodes in Mahabharata, as for

example Ashvatthama killing the sleeping sons of Draupadi, are concerned with a

departure from the rules of war. These departures are a turning point in history

which usher in the Kali age, the age of iron. Kali yuga is considered to have

begun with the great war between the Pandavas and Kauravas which destroyed the

old order.

|

| Ruins of ancient hindu city in Mohenjo-Daro 3000? BC |

The actual date of the

war, along with so many other historical aspects of Mahabharata lore, is much

disputed. According to the scholarship of no less than Bhaktivinoda Thakura,

writing in 1880 in his Sri Krishna Samhita, “It may be understood that the

battle of Kurukshetra took place 3,791 years from today. Dr. Bentley Sahib

calculated the position of the stars and decided that the battle took place

1,824 years before Christ.

|

| Ruins at Mohenjo-Daro, India, 3000? BC |

The future swanlike scholars can determine the

correct figures after further research.” Dr. C.V. Vaidya of the University of

Bombay writes in his 1905 publication, “The Mahabharata: A Criticism,”

discusses a number of possible dates for the antiquity of the actual war

described in Mahabharata.

|

| Harrapan Ceramic Vessel 2600-2400 BC |

He writes,”the

earliest date assigned to the Mahabharata war is that fixed by Mr. Modak on the

basis of some astronomical data found in the Mahabharata. He thinks that the

vernal equinox at the time of the war was in in Punarvasu and hence about 7,000

years must have elapsed since then. Some thinkers, following the opinion of Varaha

Mihira, believe that the battle was fought in 2604 B.C. European scholars on

the other hand believe in the authority of a shloka in the Vishnu Purana that

the war took place in about 1500 B.C. Mr. Dutta gives 1250 B.C. as the date of

the Kuru Panchal war on the basis of the Magadha annals which show that

thirty-five kings reigned in Magadha between the Kuru-Panchal war and the time

of Buddha. …The orthodox opinion, however, is that the war took place in 3101 B.C.,

calculating on the basis of the generally accepted belief in India that in 1899

A.D., five thousand years had elapsed since the beginning of the Kali-age. We

agree with this orthodox opinion on the basis of both internal and external

evidence.”

|

| Ancient ruined city of Mohenjo-Daro |

A modern consideration

of astronomical proof gives the date that the Kurukshetra war ended and

Kali-yuga as February 18, 3102 BCE at 2:27:30 am, based on the Surya siddhanta’s

mention that during the change of Yugas, all 7 planets will line up along the

elliptic of the Earth’s annual path in the constellation of Pisces, just before

Aries on a Phalguni Amavasya day, the last day of the year.

As Bhaktivinoda Thakura put it, “The future swanlike scholars can determine the

correct figures after further research.”

Whatever the actual date

of the Mahabharata War, it seems clear that the epic Sanskrit poem, has gone

through at least three major editions before coming down to us in its present

form of about 100,000 Sanskrit shlokas.

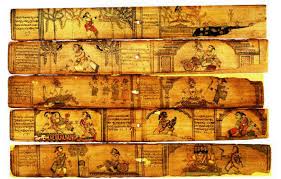

|

| Ancient version of Mahabharata |

According to my best

research on the subject, the epic Mahabharata has evolved from a core of about

8,000 verses to its present immense size of about 100,000 shlokas, between the

time of the actual Mahabharata war, sometime between 3100 and 1000. B.C. How did this evolution take place?

The Mahabharata is a

vast work. According to the Mahabharata itself, its author is Vyasa. The work was narrated in its entirety within

an oral tradition by three great narrators: Vyasa himself, Vaishampayana, his

pupil, and Sauti, another of his disciples.

Vyasa teaches the story to Vaishampayana who

relates it to the King Janamejaya at his snake sacrifice. When Janamejaya asks

questions to Vaishampayana, the narrative grows and changes. This amplified

version was heard by Vyasa and taught to Sauti, or Suta Goswami.

In this way the work as

edited by the original author Vyasa may be said to have given rise to a second

edition. This second edition was again taught by Vyasa to his other disciple,

Sauti, or Suta Goswami.

When again Sauti tells

the story of Mahabharata to Shaunaka Rishi and the sages of Naimisharanya, many

new questions arose which had not been answered by the second edition. In this

way, through the narration of Suta Goswami, a third edition was developed. This

third edition with a few minor corrections passed through the mind and heart of

Vyasa to the transcendental tusk of Ganesh and was inked in Sanskrit some time ago

in antiquity, between the 11th and 4th Century before the

Common Era.

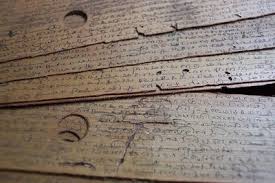

While the actual hard

copy in Sanskrit that we refer to today was canonized sometime between the 11th

and 4th Century, a living oral tradition was communicated by

brahmanas from teacher to disciple as well.

The discrepancies between oral and written traditions were resolved by

the final text which was inscribed on palm-leaves and distributed throughout

India by the brahmanas determined to preserve this ancient history.

Since the brahminic

tradition was challenged by the authority of the Guptian kings who promoted

Buddhist thought, the historic records pertaining to the origins of Mahabharata

were mostly destroyed. And so all historic scholarship as to the authentic

dates of the Kurukshetra war are based to some degree in speculation and

linguistic analysis. More on this later.

Different versions or "Editions" of the Mahabharata

the "Jaya" version: 8,800 verses

Based on some of this

scholarship, we can say that the original Mahabharata was considered as an

Itihasa or history. Its character was less didactic than the work we have

today. The original name of the work was “Jaya!” or Victory!. This name is

derived from the invocation,

नारायणं नमस्कृत्य नरं चैव नरोत्तमम् ।देवीं सरस्वतीं व्यासं ततो जयमुदीरयेत् ॥ (४)

nārāyaṇaṁ namaskṛtya naraṁ caiva narottamam |

devīṁ sarasvatīṁ vyāsaṁ tato jayamudīrayet || (4)

“As we first bow to

Narayana, who is Krishna, God Himself, and

to Nara as well, the most exalted male being, to the goddess of learning

Saraswati, and to Vyāsa, author of the work, before we utter the story of triumph,

or Jaya.”

Here, the word Jaya, or “Triumph” refers to the work

itself, and “Jaya” is considered to be the original name of the poem, penned by Vyasa himself.

In the introduction to

the work, the Adi Parva, the different editions of Mahabharata are described by

Sauti, while mentioning that the Mahabharata may be delivered in different

lengths without diminishing its value.

At the beginning of the Adi Parva, while

giving his own version, Sauti tells the sages at Naimisharanya,

“The Rishi Vyasa published this mass of knowledge in both a detailed

and an abridged form. It is the wish of the learned in the world to posess the

details and the abridgement. Some read the Bharata

beginning with the initial mantra (invocation), others with the story of Astik,

others with Uparaichara, while some Brahmanas study the whole… I am aquainted with eight thousand and eight

hundred verses, and so is Shukadeva and also perhaps Sanjaya….Vyasa

executed the compliation of the Bharata,

exclusive of the episodes originally in twenty-four

thousand verses; and so much only is called by the learned as the Bharata.

Afterwards, he composed an an epitome in one hundred and fifty verses,

consisting of the introduction with the chapter of contents. This he first

taught to his son Shukadeva; and afterwards he gave it to others of his

disciples who were possessed of the same qualifications. After that, he

executed another compliation, consisting of sixty hundred thousand verses. Of

those, thirty hundred thousand are known in the world of the Devas; fifteen

hundred thousand in the world of the Pitris: fourteen hundred thousand among

the Gandharvas, and one hundred thousand in the regions of mankind. Narada

recited them to the Devas, Devala to the Pitris, and Suka published them to the

Gandharvas, Yakshas and Rakshasas; and in this world they were recited by

Vaishampayana, one of the disicples of Vyasa, a man of just principles and the

first among all those acquainted with the Vedas. Know that I, Sauti, have also

repeated one hundred thousand verses.

How did the original

work of 8,800 verses become 100,000 verses? The very expansion of the

Mahabharata from 8,800 to 100,000 verses defies a “fundamentalist” approach.

How could it be possible for a disciple to expand his guru’s version from a

terse 8,800 verses to a bulky 100,000 verses. The Mahabarata in translation

runs to about 2 million words in English. Who authorized Sauti to create a

longer version of the work?

The "Bharata" version: 24,000 verses

The 8,800 verse

first edition of anusthab shlokas in Sanskrit composed by Vyasa and mentioned by Sauti becomes a second edition when it

is narrated by Vaishampayana Rishi, a disciple of Vyasa.

Vaishampayana had been taught the

poem along with his godbrothers Sumantu, Jaimini, Paila, and Shukadeva Goswami, the son of

Vyasa himself.

According to the final

edition of Mahabharata, each one of these five disciples published a different

edition of the work. Vaishampayana’s edition of Mahbharata differs from the

original work by some 16,000 Sanskrit verses. On the evidence of the Adi Parva

quoted above, it seems that Vaishampayana’s “Bharata” version ran to about

24,000 verses.

The "Mahabharata" of Sauti

So, the original version expands from 8,800 to 24,000 by the

reckoning of Sauti. Sauti, our final narrator who gave the work its ultimate form of

100,000 verses as recited before the sages of Naimisharanya headed by Shaunaka somewhere after 1000 BC.

Sauti says, “Know ye

Rishis, that while Vaishampayana was the first reciter of Mahabharata in the

human world, I have recited the work of

Vaishampayana in 100,000 shlokas.” The

current edition comes down to us in the form we know now it with a preface, and

introduction and a table of contents. With Sauti, or Suta Goswami as he is

known in the Bhagavat Purana, for he also narrates this poem of Vyasa, we

arrive at the fixed form of Mahabharata which in fact contains about three thousand

less shlokas than that given by Sauti (96,836 to be exact.) It was perhaps

Sauti himself who gave the name “Mahabharata” to the work, changing it from “Bharata,”

or “Jaya” as in the original version given by Vyasa.

In short, the present

Mahabharata may be considered as an original composition of Vyasa called "Jaya" in 8,800

verses, edited in a 2nd edition or Bharat edition by his disciple Vaishampayana in

24,000 verses and expanded, edited with table of contents, preface and

introduction in 100,000 verses as Mahabharata by Sauti, or Suta Goswami as he is also known in a final 3rd

edition.

Whatever the

contribution made by Vaishampayana and Sauti, the authorship of Mahabharata is

generally attributed to Vyasadeva Himself. No reason exists to reject the

authority of tradition. On the other hand, Vyasa is believed to have edited the

Vedas which predate the Mahabharata considerably. The brahmanas mentioned in

the Mahabharata are “well-versed in the Vedas.” Vyasa’s father Parashara was

considered “well-versed in the Vedas.” How could the father of Vyasa be “well-versed”

in a book that his son has yet to write?

That there really

existed a Rishi named Vyasa who was the son of Parashara has been confirmed by

a number of reliable scriptural sources outside the Mahabharata, as for example

the Yajun Kathaka. There is no reason to doubt that this Vyasa wrote the epic poem

and did so on the basis of his own personal knowledge. One of the remarkable

features of the Mahabharata is the intimate detail of events, characters, and

the quotidian life of the period. Only an eye-witness could have described the

events and places of thousands of years ago with such an eye to detail. People

and places are often mentioned as being so well-known as to have no need for

introduction. As a result of Vyasa’s gift for description the reader feels the characters

in Mahabharata must be living breathing souls of flesh and blood.

Often the descriptions

in Vyasa’s narrative strike us as no less than fossils whose outline reveals

the reality of a lost and forgotten ancient civilization. An impartial reader concludes that this

narrative was written from a personal acquaintance with the characters and an

intimate relationship with the heroic deeds. In fact, far from being a collection of

mythological fairy stories, much of the Mahabharata reads like the realistic

story of heroes struggling with historical problems, much like the Canto del

Cid, the primordial epic in the Spanish language.

But if there was a

historical Vyasa who wrote the Mahabharata, what is his relation with the original

Vyasa who wrote the Vedas? Was there another Vyasa who compiled the edited

version of Mahabharata given by Sauti and issued a fourth edition?

But if there was a

historical Vyasa who wrote the Mahabharata, what is his relation with the original

Vyasa who wrote the Vedas? Was there another Vyasa who compiled the edited

version of Mahabharata given by Sauti and issued a fourth edition?

Bhaktivinoda Thakura’s point of view is well

worth considering:

"When the one Veda

became greatly expanded, then Vyasadeva, after duly considering the subjects,

divided the Veda into four and wrote them in book form. This took place a few

years before King Yudhisthira s reign. Then Vyasadeva s disciples divided those

words among themselves…

"…It is said that the

Mahabharata was composed by Vyasadeva, and there is no objection to this. But

it cannot be accepted that the Vyasa who divided the Vedas and received the

title Vedavyasa at the time of Yudhisthira was the same Vyasa. The reason for

this is that in the Mahabharata there are descriptions of kings such as

Janmejaya, who ruled after Yudhisthira. There are specific references about the

Manu scriptures in the Mahabharata, therefore the present day Mahabharata must

have been written some time after 1000 B.C.

" From this it appears that Vedavyasa first made

a draft of the Mahabharata, and later on another Vyasa elaborated on it and

presented that under the name of Mahabharata One learned scholar from the sudra

community named Lomaharsana recited Mahabharata before the sages at

Naimisaranya. Perhaps he created the present day Mahabharata, because during

his time the original 24,00 verses that were written by Vyasadeva were expanded

to 100,000 verses.

"Since there is no

special mention of Buddha in the Mahabharata it is understood that Mahabharata

was recited by Sauti before the reign of Ajatasatru and after the reign of

Brhadratha's descendants. If we study the descriptions of Naimisaranya, then we

come to know that when the peaceful rsis saw the end of the Candra and Surya

dynasties, they felt unprotected due to the absence of ksatriyas. Therefore

they went to the secluded Naimisaranya and passed their lives discussing the

scriptures. There is one more belief about the assembly of Naimisaranya.

For some time after

the battle of Kuruksetra and before the coronation of King Nandivardhana the

Vaisnava religion was very prominent. The main conclusion of the Vaisnavas is

that every living entity has a right to cultivate spiritual life.

"But according to the

opinion of the brahmanas, persons of castes other than brahmana are ineligible

for liberation. Sober persons of other castes may be born again as brahmanas to

endeavor for liberation.

" Because of these two conflicting opinions, the

Vaisnavas highly regarded the scholars of Suta Gosvami’s line and thus

established them at Naimisaranya as superior to the brahmanas Some of the brahmanas there who were less

qualified and controlled by wealth also accepted the scholars of Suta s line as

superior. Those less qualified brahmanas defied the doctrines of karma kanda and accepted Suta as their

spiritual master.

"They took shelter of

Vaisnava religious principles, which are the only means of crossing the influence

of Kali, the abode of sin. Anyway, that assembly gathered long after the battle

of Kuruksetra. There is no doubt about this. (Kedarnatha Dutta,, Bhaktivinoda Thakura Shri Krishna Samhita 1880, Calcutta)

Sauti’s narration of

Mahabharata was heard by the sages of Naimisharanya forest at the twelve year

sacrifice of Shaunaka. If Sauti and Suta are the same person, Suta Goswami is

also the narrator of Bhagavat Purana and a disciple of Vyasa who narrated his

conclusions to Shaunaka Rishi and the sages of Naimisharanya.

The Mahabharata

narration of Sauti or Suta Goswami as heard by Shaunaka was later compiled by

Vyasa as the final edition of Mahabharata. Sauti heard the story of Mahabharata

from his guru Vyasa. Vyasa’s version as heard and narrated by Sauti includes

the version of Vaishampayana Rishi as told to Janamejaya.